CHAPTER XVII

This is Chapter XVII of the serialisation, the wording reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, on Tuesday 4th June 1889.

The Dying Speeches of the Political Martyrs – Hardie’s ‘Noble Spirit’ – The Effect of an “Amen!” – Decapitation of the Bodies – A Bungling Executioner – The Mystery of the Headsman Revealed – “Granny Duncan’s” Kindly Action – A Night Internment in Stirling Churchyard – An Interesting Spot

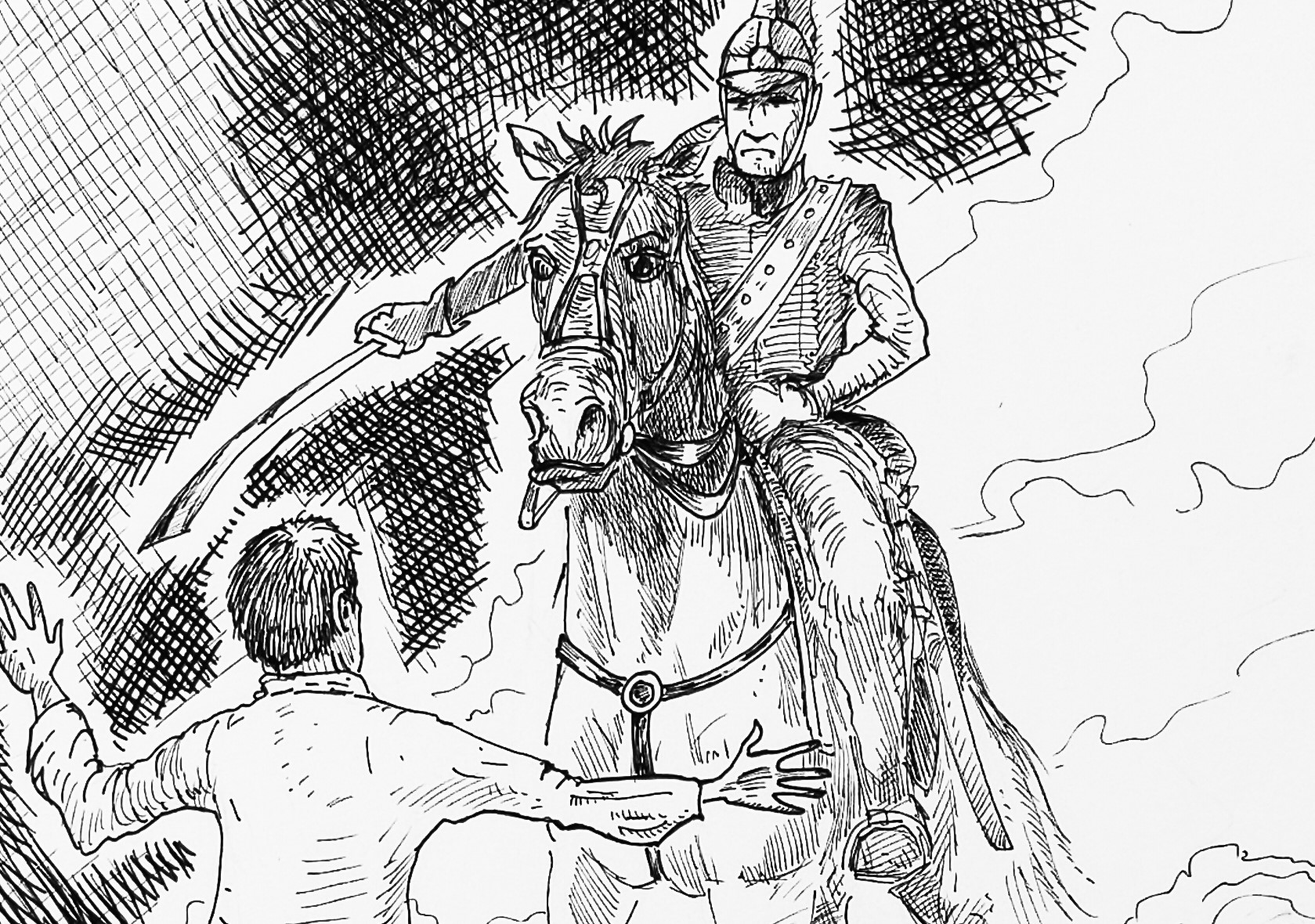

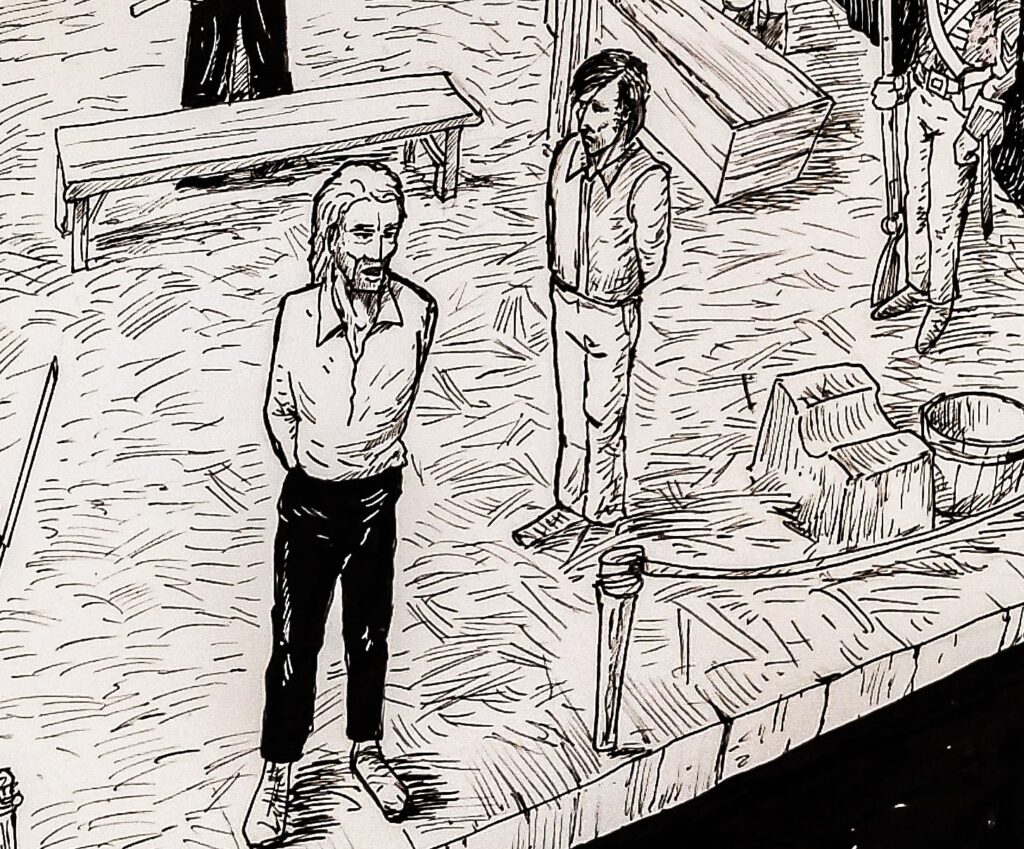

With steady and unfaltering steps, Baird and Hardie advanced to the scaffold. Through Mr Bruce, Baird asked permission from Sheriff McDonald to address a few words to the assembled multitude. Mr McDonald enquired what would be the subject of his address, at the same time stating that nothing political would be allowed. “What an unfeeling scandalous interruption was this!” exclaims Peter MacKenzie, “as if they were afraid of the words of a dying man.” According to the Journal report, Baird solemnly declared on the word of a dying man, that he would only speak for eight or ten minutes on the Bible, and that Hardie made a similar request, also solemnly declaring that he would make no reference to political subjects, and that his wish was to press upon those who were present the propriety of paying attention to religion and their Bible. Mr Bruce informed the Sheriff that both men had most solemnly protested to him that morning against any intention on their part to speak on political subjects – on the contrary, they had only in view to recommend religion, the Bible, and sobriety to those who might be present. Upon this solemn declaration and representation, continues the Journal, permission was granted them upon the condition that when they should transgress the agreement they should no longer be allowed to proceed. It seems to have been expected that the unfortunate men would say something disagreeable to the authorities, and whatever promise they may have given, they had evidently made up their minds to publicly declare that they were political martyrs.

Baird spoke first. Bowing to the crowd, he addressed them in nearly the following words: – “Friends and Countrymen, – I dare say you will expect me to say something to you of the case”, (no doubt meaning cause) “which has brought me here, but on that I do not mean to say much, only that what I have hitherto done, the matter that brought me here, was for the cause of truth and justice. What I would wish particularly to direct your and my attention to is, to that God who is the judge of all mankind, and all human action, and to Jesus Christ, the Saviour of men. I have never hurt anyone – I have always lived and innocent life – and as that is well known to those who know me, I shall say no more about it. I am not afraid of the appearance of a scaffold, or of a mangled body, when I think of the innocent Jesus whose living body was nailed to a cross, and whose wounds I have often made to bleed afresh for my sins, and through whose merits I hope for forgiveness. My friends, when you go from this place, I entreat you not to go to change-houses, but to go home and take up your Bibles, not as a ballad, or as the production of men, but as the work of God Almighty.” After recommending them to lay aside folly and observe the Sabbath by attending Church, Baird suddenly stopped, and turning round stepped backwards to look at Mr Bruce’s watch to see if he had exceeded the time he had allotted to himself.

Hardie, who during Baird’s address had been kneeling by the railing apparently in prayer, rose hastily and walked to the opposite side of the scaffold – the right-hand side, from which Baird had spoken – and in his turn addressed the crowd. He commenced with the word “Countrymen!” and proceeded to remark, as Baird had done, on the cause that had brought him to the scaffold. Then he cried with a loud voice – “I declare before my God I die a martyr in the cause of truth and justice.” No sooner was this uttered than someone in the crowd (whom we need not suppose with the Journal reporter, to have been connected with pickpockets) shouted “Amen!” The word was caught by others, and repeated by some person in a window opposite, and there were huzzas, shouts, and other marks of approbation. Some of those at the outskirts of the crowd, not knowing what was passing near the scaffold, and probably fearing a charge by the military, began to fly in all directions, but order was soon restored, the excitement lasting only a few seconds. When Hardie made use of the expression above-quoted, Sheriff McDonald addressed him as follows: – “Hardie, remember, sir, your solemn promise; I cannot permit you to proceed in this manner; if you attempt it, I must call the executioner to do his duty.” Hardie bowed to him and said – “I had determined to say so much even if you had not given me permission.” (Thus says the Radical historian, his noble spirit sustained him to the last.) “I wish now to speak to them of the bible and of religion.” “My friends,” he said turning to the crowd, “I should be sorry if anyone should be hurt today. I recommend it to you not to think of us, but to be peaceable and to pay attention to your Bibles; and in place of going to change-houses to drink to the health (meaning, no doubt, “Memory”) of Baird and Hardie, to retire to your devotions.”

The executioner then stepped forward and adjusted the ropes, both men fervently praying the while. When the ropes were over their necks and the white caps drawn over their faces, a most affecting prayer was offered up by Mr Bruce, during which he took occasion to say that to the men who were so soon and suddenly to leave the world, he trusted that death would be disarmed of its sting, and that they might be enabled to cry, “Oh death, where is thy sting! Oh grave, where is thy victory!”, which words the prisoners repeated loudly and fervently. They then for a few moments prayed silently and at 11 minutes past 3 o’clock, Hardie, having with his left hand seized the right hand of Baird, dropped the handkerchief, the bolt was drawn, and the victims of villainy and cowardly panic were launched into eternity. Their hands were united for about a minute; they scarcely gave a convulsive struggle, Baird’s Bible, which he held in his left hand, dropped when the trap gave way, and was afterwards preserved by his friends. Hardie, while in the court-room, requested his Bible be given to his mother.

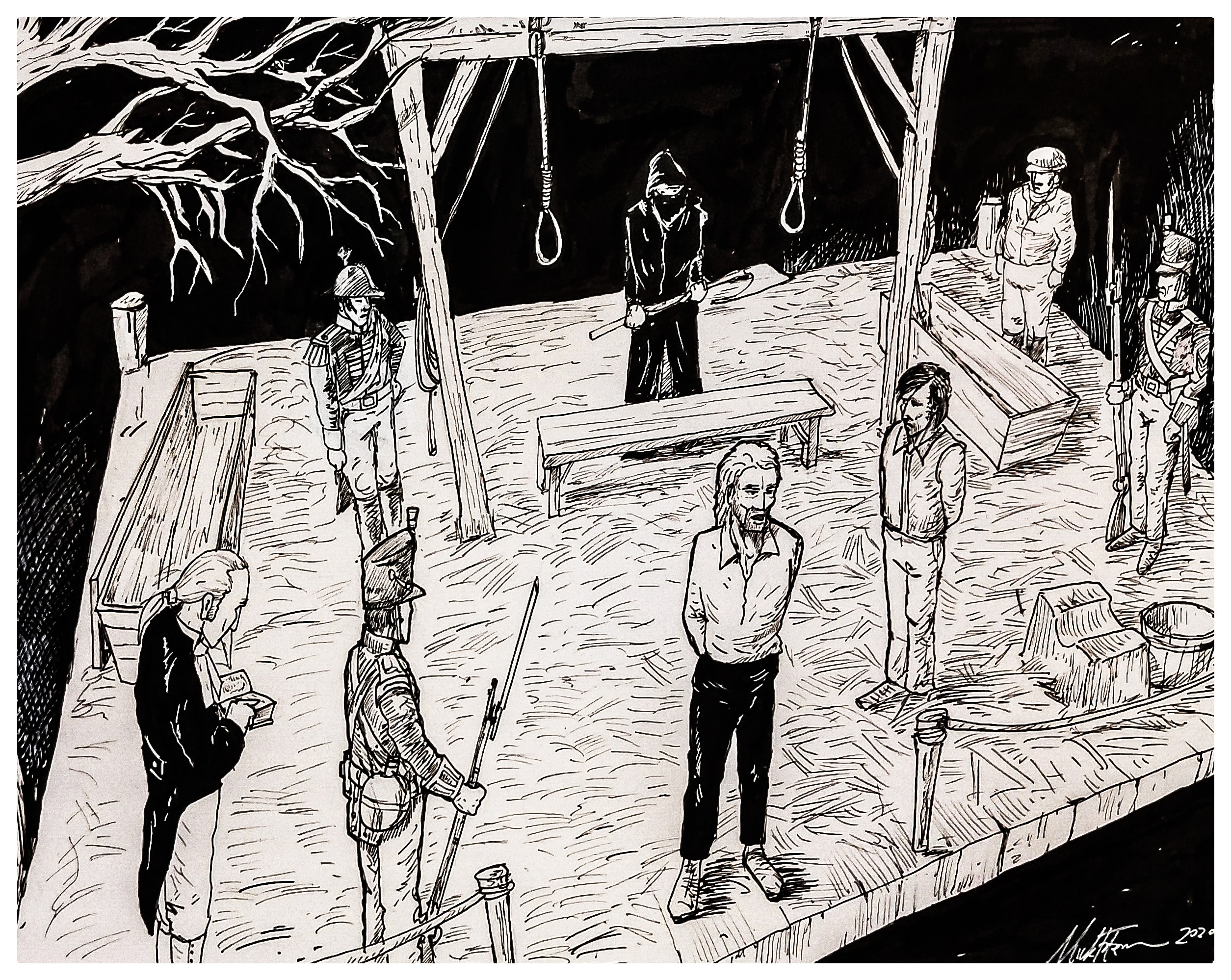

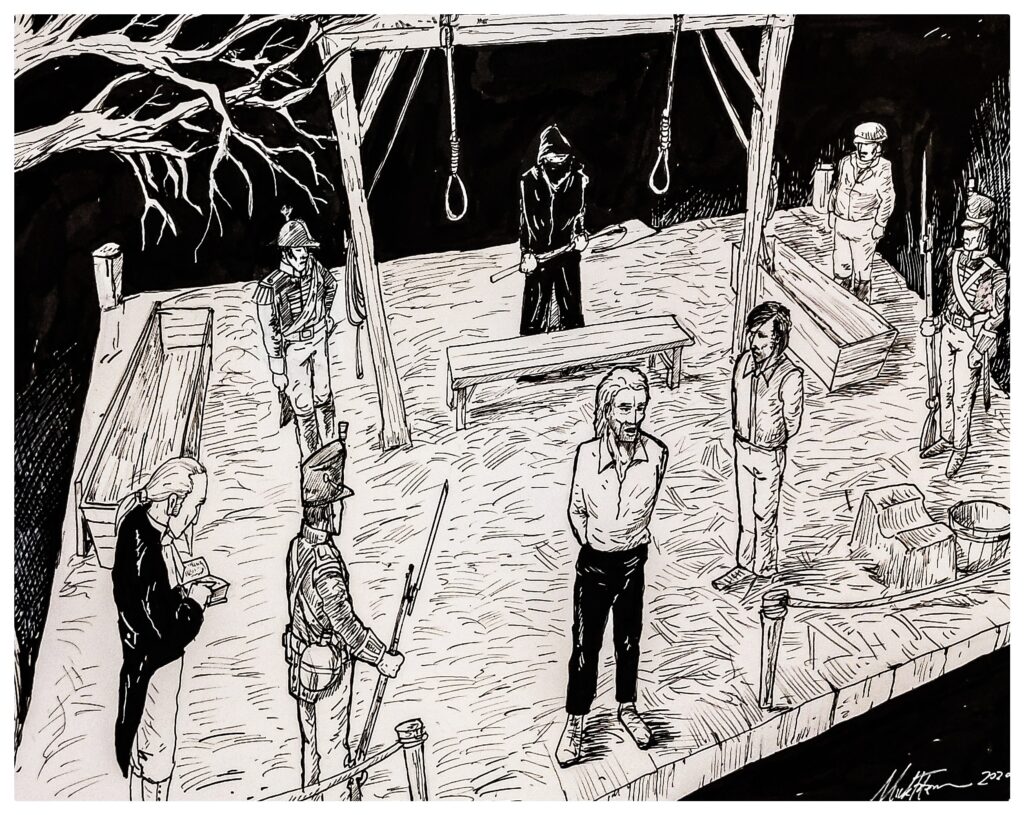

After hanging about an hour, the bodies were cut down and placed upon their coffins, with the face downwards, the neck resting on the block, and head hanging into the pit. Another part of the sentence was to be carried out – a part which might well have been omitted. The headsman appeared with his axe to sever the heads from the lifeless trunks. He was a little man, apparently about 18 years of age, rather delicately made and well-looking. He wore a black crape over his face, a black serge gown, and a boy’s hairy cap. He did not seem very capable for the hideous task he had undertaken, for he was exceedingly agitated. On his appearance a shudder ran through the crowd., and cries of “Murder! Murder!” were raised. Hardie’s body was the first operated upon. From his agitation and consequent weakness, the executioner had to give three blows with his axe before he could sever the head from the body. He then held up the head with both hands, and evidently with an effort, exclaimed – “This is the head of a traitor!”. Recovering some confidence when the cries had ceased, he decapitated Baird at two strokes, holding up the head in the same manner and using similar words. Having performed his duty he hastily retired. He was observed to tremble greatly and was heard to say, “I wish to God I had not had it to do.” After divesting himself of his mask, &c., in the jail he made his way through the crowd unobserved and left the town immediately. Next morning a stranger who was going away with the Edinburgh mail coach was mistaken for the headsman and was hooted and mobbed. Who the headsman really was remained a mystery as impenetrable as that of the “Man with the Iron Mask” for a long time, but Mr MacKenzie, so often quoted in this “Story of Baird and Hardie” ascertained that he was a medical student or surgeon named Moore, who lived in Bridgegate, Glasgow. He was last heard of in July 1831, when he resided in Mayroe, co. Londonderry, Ireland.

The mangled bodies of the political martyrs were not allowed to be delivered over to their sorrowing relative. The Glasgow authorities afraid of a public funeral and procession, sent an express to Stirling begging the Sheriff to order the bodies to be detained here. It is said, however, that the Sheriff’s warrant contained instructions for the internment of the bodies in Stirling Churchyard. We are informed that the heads were reverently laid with the bodies by a Castlehill woman, afterwards known as Granny Duncan, whose descendants are still among us. Her kind action was not forgotten by the relatives of the unfortunate men. The funeral took place at nine o’clock the same night, and was attended by the Burgh Magistrates. The internment was made in a piece of vacant ground, probably used for the burial of the poor, a little to the north of the East Church. In 1826, Baillie Ronald informs us, this piece of ground was purchased by Mr Chalmers, mason, father of the famous town bellman. His family burying place was in St. Ninian’s Churchyard, where he himself lies, but his sympathy for the Radicals was so strong and his grief for their sad fate so great, that he acquired the ground and marked it with pawl-stones inscribed with the letters “J.B.” and “A.H.”. We will probably have something more to say about this interesting spot in our churchyard in a future chapter.

To be continued…