Tomorrow, Tuesday the 30th November 2021, Craig Murray will be released from HMP Edinburgh, having served four months of an eight-month prison sentence imposed earlier this year. The remaining four months will be served in the community under licence. Mr Murray, journalist and former British diplomat, was imprisoned after being found guilty of contempt of court relating to his coverage of the trial of Alex Salmond and claims that it could (potentially) lead to the ‘jigsaw identification’ of complainants. In 2020, the former First Minister was acquitted of charges of sexual assault. The imprisonment of Craig Murray raises many questions about the Scottish criminal legal system, specifically, and the future of Scotland more generally. And we should all be concerned.

There are a number of unusual and troubling aspects to this case. Mr Murray did not name any of the complainants in the case. Instead, his conviction relates to the possible ‘jigsaw identification’ that could potentially be construed from coverage of the case. Although Craig Murray is, as far as we know, the first person in the world to be convicted of jigsaw identification, he is not the only person to have received a prison sentence for charges relating to the Alex Salmond trial. In February 2021, Clive Thompson was jailed for six months by Lady Dorrian for naming two of the complainants on Twitter, breaching a court order put in place to protect the anonymity of the complainants (in Scotland, anonymity is not an automatic right but has to be applied by the court).

In March 2020, shortly after the Salmond verdict was delivered, journalist Mark Hirst was charged under Section 31 (1) of the Criminal Justice and Licensing Act, for a ‘crime’ formerly known as Breach of the Peace. Hirst was accused of using a term (‘reap the whirlwind’) in relation to the complainants in the Salmond case. His phrasing was reported to Police Scotland by Rape Crisis Scotland who claimed that it represented a ‘threat’ to the complainants. After being found by Sheriff Peter Patterson to have no case to answer on the 7th January 2021, Hirst’s lawyer, Gordon Dangerfield, lodged a malicious prosecution case against the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscals Service.

The protection of complainants is an extremely important issue, of that there is no doubt, and the law in Scotland differs from that of England and Wales, where anonymity is automatic. However, Mr Murray’s case raises a number of significant concerns about Scottish ‘justice’ and deeper questions relating to the fundamental objectives of the criminal legal system. In many ways, the imprisonment of Craig Murray epitomises the inherent problems and cultural rhetoric of punitive penality in Scotland, and the rest of the UK. It exposes many of the very concerning issues that underpin the operation of the legal system.

Unaccountability in the Scottish Legal System

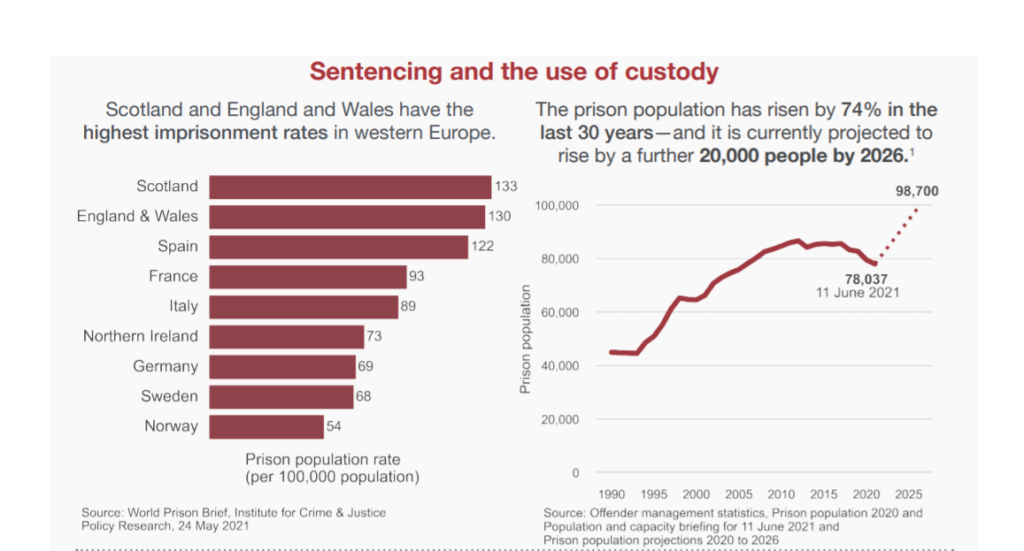

We do not intend to delve into the wider issues surrounding the charge or the trial that it related to. However, the imprisonment of Craig Murray, for this unusual ‘civil charge’, flies in the face of wider calls from politicians, policy makers and academics, to reduce the prison population in Scotland. It is worth noting that despite claims to progressive democratic nationhood, Scotland has the highest rate of imprisonment (as a percentage of the population) in Western Europe. Scotland’s imprisonment rate is 133 per 100,000 population (which compares to 130 per 100,000 in England and Wales and 54 per 100,000 in Norway – a country that we often aspire to as a potential model for an independent Scotland). The use of remand is a particularly troubling feature of the Scottish penal landscape.

Many of Scotland’s prisons are overcrowded, and concerns about prison regimes include drug use and associated violence, poor infrastructure and the moth-balling of prison work programmes and educational opportunities. The recent Covid-19 lockdowns seriously affected the prison system – with lengthy restrictions imposed on rights to association, activities and visits. Covid-19 outbreaks were reported in many prisons, including HMP Edinburgh into which Craig Murray was admitted as a civil prisoner.

The high rates of imprisonment in Scotland have not gone unnoticed. In 2019, in response to ongoing criticism from many quarters, the Scottish Government introduced a presumption against short prison sentences. Initially (since 2011) intended to prevent imprisonment on a custodial sentence of less than 3 months, it was soon extended to a presumption against prison sentences of less than one year. This, it was hoped, would encourage and guide sentencers to make greater use of already existing community-based disposals and avoid the constant and detrimental ‘churn’ of short sentences. It was based on a recognition of the harm imprisonment causes to individuals, families and communities; particularly short periods of custody – a claim widely supported by national and international research.

The punishment of Craig Murray raises a number of questions about the use of imprisonment in Scotland today. To select only a few:

- The Scottish Government introduced a Presumption Against Short Sentences (Scotland) Order 2019, suggesting non-custodial sentences should be used for periods of less than 12 months.

- The Prison Inspectorate in Scotland, along with academics, campaign groups and human rights organisations, have highlighted the need for Scotland to reduce its prison population, which is the highest in Western Europe.

- It was acknowledged by the Scottish Government that the prison population should be reduced by releasing ‘non-violent offenders’ in order to combat the potentially fatal effects of COVID 19 – despite this, there has been a continued use of short-term custodial sentences at a time when infection rates were out of control in most, if not all, of Scotland’s prisons.

- Craig Murray’s defence team submitted detailed information related to his deteriorating health, with accounts suggesting that his overall medical condition, as well as some very particular health problems, made a custodial sentence a high-risk disposal. Although Craig Murray was deemed too ill to complete a sentence of punishment in the community, he was imprisoned at the height of widespread COVID-19 infections.

This case, and the fact that there are many similar cases, where less well-known individuals are subjected to the frequently unaccountable criminal legal system should make us all concerned at the administration of ‘justice’ in Scotland.

The case of Craig Murray speaks to growing concerns about journalistic freedom, selective prosecutions and political influence. But his imprisonment raises deeper questions about the punitive aspects of nationhood that are features of contemporary and historical Scotland. This underlying Scottish punitiveness is not a new phenomenon. In the 16th and 17th Centuries, Scotland accused, executed and burned more people, mainly women, under the Witchcraft Acts than most other countries in Europe; a staggering four times as many people were executed in Scotland than England, despite our neighbour having at least five times the population. When taken in context, it is clear that the Scottish appetite for punitive paternalism and a politically motivated sense of vindictiveness is not new.

From Scotland’s vigilante gangs at the bottom of the social structure to our malicious juridical class at the top, our current thirst for punishment is unrivalled in Western Europe. When it comes to witch-hunting (literally), scapegoating and punishment, Scotland has, for centuries, been a world leader. The optimism that sprung from the 2014 independence referendum led a number of people to (re)present and (re)imagine a Scotland that was more ‘socially just’ than its neighbours and one that had a long history in which ‘egalitarian’ tendencies were deeply ingrained.

A Punishment System Beyond Reform

Tomorrow Craig Murray will be released back into the care of his family and friends, who have campaigned tirelessly against his imprisonment and for his early release. It is important, however, to stress that the concerns that this campaign has focused on and highlighted should not be confined to the case of Craig Murray. The problems identified are interwoven into the unaccountable authoritarian state itself, and only serve to illuminate the unhealthy relationship Scotland has had, and continues to have, with the regime of punishment. We have no doubt that many people involved in the campaign of support for Craig Murray will share a vision of a future Scotland that is radically more progressive and ‘fair’ than the one that currently exists.

This will require some radical reimagining as well political innovation, if not revolutionary changes. We hope that the needless imprisonment of Craig Murray – for what purpose could it usefully serve? – does at least inform the wider recognition of the utter pointlessness of imprisonment for all but the most dangerous individuals in society. We hope that Craig’s experience of prison will be used as a vehicle to persuade more and more people that the punishment system in Scotland is beyond reform.

As far as the realisation of a better Scotland is concerned, we urge that penal abolitionism be placed at the very centre of this vision.