Recent events surrounding the relentless partying that took place at Downing Street while the rest of the country was in lockdown, have raised questions about the role of the police in contemporary society. Perhaps the most common complaint to arise from the Party-Gate ‘scandal’ is that the powerful are not held to account in a way that is consistent with everyone else.

The reason that the most privileged groups in society are often exempt from the rules that they themselves make in the service of their own narrow interests, is down to the issue of policing. At the very heart of this issue lies the entirely mythical notion that the police exist to serve and protect the public. This misplaced assumption could not be further from the truth. Indeed, when the police occasionally appear to be protecting the public (and when they do it tends to be significantly amplified in the media) it is largely the exception that proves the rule.

This blog will, in order to better understand the police and policing in a global context, make the following points:

- The police exist almost exclusively to protect the material and symbolic interests of the powerful.

- Police forces are ultimately political institutions. Since the 1960s the police have actively been spying on and infiltrating some of the most benign political and environmental groups in the UK. As an institution, the police, like the media and the mainstream political parties, are responsible for the maintenance of the status quo.

- Whatever the political context, as illustrated by the actions of police forces internationally, the police are always the state police. Irrespective of the country they operate in or the political system within which they are deployed, the police, through their powerful federations and lobby groups, universally demand two things. On the one hand they demand more powers and resources, and on the other hand they call for more discretionary powers, reducing independent oversight and accountability.

This blog will develop these points in turn.

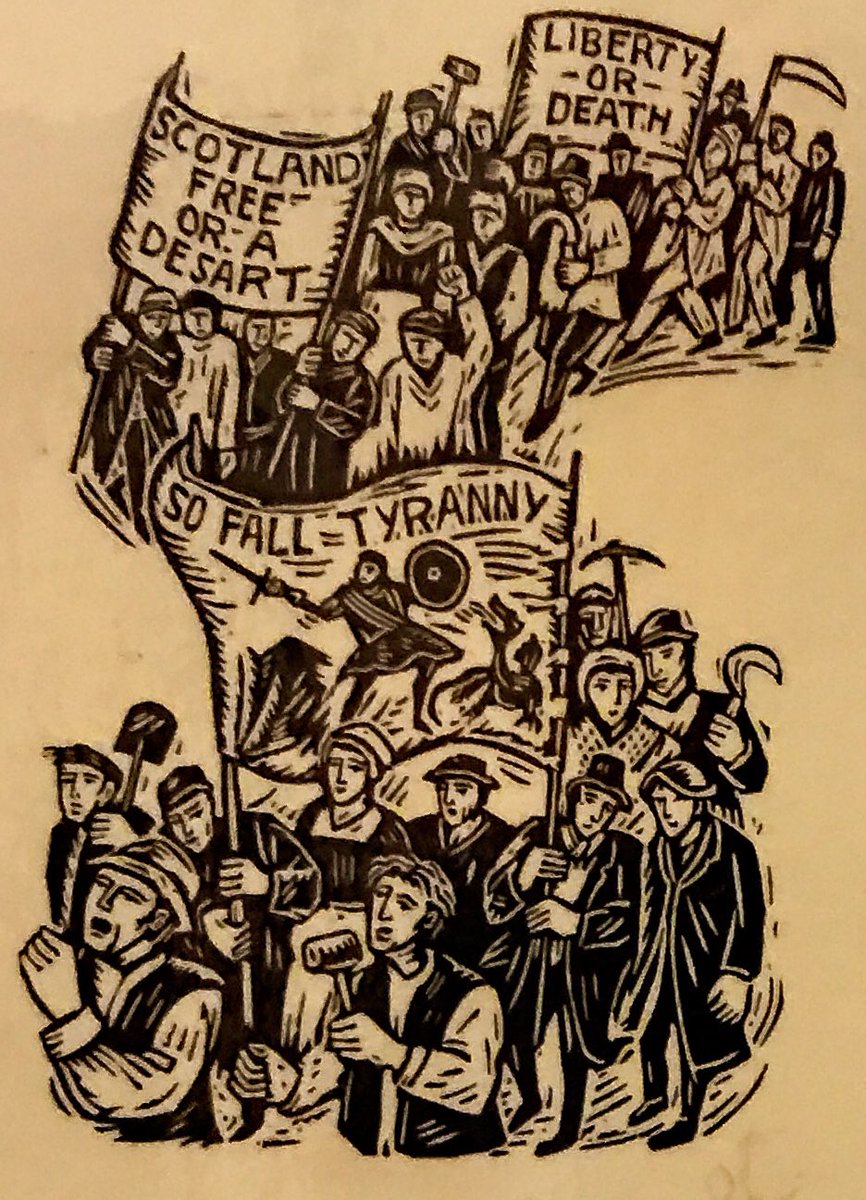

The Origins of Policing – the subjugation of colonial populations

Julian Go, from the University of Chicago, claims that all current forms of policing have their origins in the forging of Empire. Being an effective means of repression, the models used for subjugating colonial populations were directly transferred to the model of policing we see today.

In the US, the form of policing adopted was an adaptation of this colonial model utilised for the repression and subjugation of enslaved populations as well as the poor. Initially set up to catch and return runaway slaves, the US police evolved into an enforcement mechanism for the maintenance of racialised capitalism.

Decades of ‘copaganda’ that has poured out of TV and film screens on both sides of the Atlantic as well as highly favourable coverage of police and policing in the media, has cemented the impression that the police are a force for good, that they exist to serve and protect the public. This cops-and-robber’s narrative – the good guys catching and bringing to justice the bad guys – is one of the most insidious misrepresentations that has pervaded public discourse, creating an entirely mythical ‘law and order’ narrative that has given shape to popular discourses on ‘justice’.

Despite increasing scepticism and a growing mistrust of the police among an ever-widening range of communities, this never seems to threaten the populist belief in law-and-order mythology that pervades almost every society, irrespective of its political system.

Political Policing – the Spycops Scandal

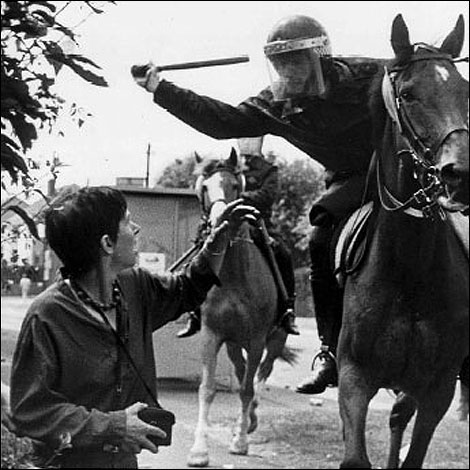

The ongoing Inquiry into Undercover Policing in the UK has shown that one key function of the police, directed by Special Branch, was to act as the eyes and ears of the UK security services, principally MI5. Since the setting up of the Special Demonstration Squad in the 1960s and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPIOU) controlled by the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), the police have been instrumental in infiltrating political and environmental groups all over the UK.

From the evidence that has been presented to the ongoing public inquiry, we now know that around 150 police officers were used to spy on over 1000 political and environmental groups across the UK since the 1960s. Anti-war groups, peace protesters, and groups campaigning for animal rights and environmental issues were infiltrated by undercover police, highlighting the extent of political influence over citizen activism. For decades, the police spied on and infiltrated left-wing political groups fighting for worker’s rights and were responsible for drawing up an extensive ‘black list’ of trade union activists which they shared with construction firms and other key industries. Not only were far right groups almost completely ignored by the police, the Inquiry has learned that a deliberate decision was made to concentrate on ‘anti-fascist groups’ that comprised large numbers of black and ethnic community members.

Racist, Misogynist and ‘Inept at Tackling Corruption’

In 1999, the MacPherson Report determined that the investigation into the Metropolitan Police response to the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence had found that the police were institutionally racist. Furthermore, subsequent evidence proved that an undercover police officer was deployed to infiltrate the Lawrence family and their campaign to obtain justice for Stephen. Rather than addressing the issue of racism in the police, the Metropolitan Police sought to cover up their operational shortcomings and to obfuscate the true extent of the problem, which as recently as 2022, police chiefs have admitted still exists today.

In 2021, a report from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services found that measures taken by the Metropolitan Police in tackling institutional corruption were ‘fundamentally flawed’. This it attributed to the arrogance, secrecy and overall lethargy of the police to take seriously, never mind tackle, corruption within the force. It found that the vetting process for the police was inadequate, that large quantities of seized items including drugs, arms and stolen cash remained unaccounted for, and that over 2000 warrant cards were in the possession of former officers, no longer authorised to use them. The report was commissioned in response to allegations of police corruption in response to the murder of Daniel Morgan in London in 1987. To date, three former Met Police Chiefs, including the recent Head, Cressida Dick have been found to have obstructed investigations into the murder of the private detective, who it was believed, was killed before he was able to expose police corruption. The two former Met chiefs before Cressida Dick, who were identified as obstructing this murder inquiry, now sit in the House of Lords.

A recent report into policing practices at Charing Cross police station, conducted by Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) and published this year, is yet more proof of the problematic nature of the police. Not only did the investigation identify a deep-seated culture of misogyny in the police, the report found that ‘extremely vulgar and sexist’ messages were ignored and continued to circulate long after they were brought to the attention of senior officers. Messages exchanged by police officers included ‘jokes’ about raping women and other violent sexist themes that were shown to be part of the daily culture at Charing Cross Police Station. The evidence clearly challenges this culture as an isolated set of incidents suggesting, rather, that these attitudes are so widespread as to be part of the very fabric of police culture across the UK.

That the police exist to keep us safe and serve the public interest is a myth so deeply embedded within contemporary popular belief that it represents a universal orthodoxy. So much work is done by the media and other political institutions to promote this myth that it has become almost unquestionable. The truth about policing, like almost all political truths, is conveniently hidden behind the relentless, meaningless noise of popular journalism that increasingly enjoys a monopoly on what lives in the public consciousness.

Statistical evidence shows that, on both sides of the Atlantic, you are more likely to be the victim of sexual assault from a police officer, than any other professional group (Richie 2017, Vitale 2018, Maher 2021, Correia and Wall 2021). A recent Panorama programme, following on from the rape and murder of Sarah Everard by a serving police officer showed that over 2000 police officers were reported for serious sexual misconduct in the UK (a problem it has been acknowledged is grossly unreported). Almost all of them have remained in post. In Scotland, of the 250 police officers investigated for serious sexual misconduct since 2019, not one was dismissed, with most returning to work and some allowed to resign, pension intact. The same is true for domestic violence. Recent FOIs have shown that not only is no action taken against police officers who abuse their own partners, they almost all return to work.

Abolishing the Police

The evidence from these few inquiries referred to above, indicates the criminogenic nature of the police. With regards to sexual harm, the evidence strongly points to the fact that women and children would be safer if we abolished the police and replaced them with community solutions that took our welfare much more seriously.

The fact that the police are, in every country and in every political context, policed only by themselves, leads to a serious problem of accountability on a truly global scale. The absolute unaccountability of the police and the authoritarian practices of policing attracts to its ranks some of the most petty and vindictive individuals in society.

This is why any talk of reform is futile. Policing is the problem. They do not exist to serve you or to keep you safe.

The unequal and lopsided policing of the parties and illegal gatherings during COVID’s lockdown period is one example among many that the police do not exist to protect anyone other than the interests of a very small powerful elite.