This is the first part of the serialisation reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, word for word, on Tuesday 12th February 1889.

Transcribed and formatted from the original microfiche by Craig.

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY.

BAIRD AND HARDIE’S NAMES PROSCRIBED – GRADUAL CHANGE OF FEELING – A GLANCE BACKWARDS – THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND ITS EFFECTS UPON THIS COUNTRY – THE “BLACK NEBS” – EARNEST REFORMERS TRANSPORTED – WATT AND DOWNIE’S CRAZY PLOT – THE STIRLING “FRIENDS OF THE PEOPLE” – LIBERAL BUT CAUTIOUS – THE CONSPIRATORS’ AGENT INTERVIEWS DR FORREST – THE DOCTOR A WITNESS AGAINST THE ACCUSED – VERDICT AND SENTENCE – THE REPUBLICAN PIKES.

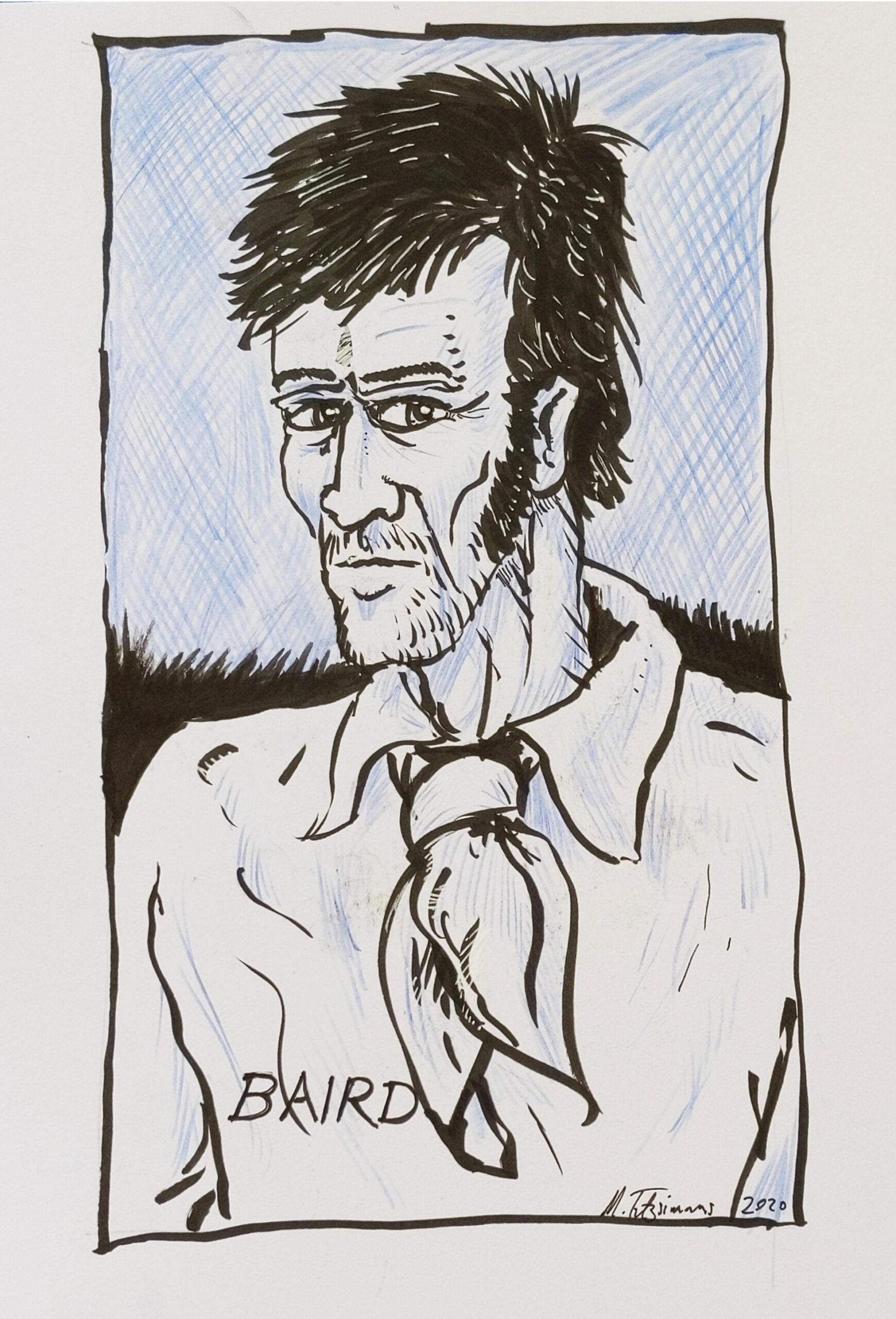

It is probable that the names of Baird and Hardie are familiar to most of our readers. They are not, so far as we know, to be found in any school book (at all events our school books were silent regarding them), nor is any prominence given to them in the various histories of Scotland. Fifty years ago it would have been considered “bad form” for an historian to notice two men in humble life who had been executed for their misdeeds, and only the most Radical of newspapers could afford to allude to them without forfeiting the good opinion of their subscribers.

After the passing of the Reform Bill of 1832, when it was seen that after all Reform was not a thing to be afraid of, public opinion became more tolerant, and Baird’s and Hardie’s names could be risked in conversation, although the high and dry Tory would be sure to turn up his aristocratic nose at the mention of such a vulgar pair. Since then Reform Bills have become comparatively common, Conservative as well as Liberal governments readily granting such concessions as the changed times seemed to require.

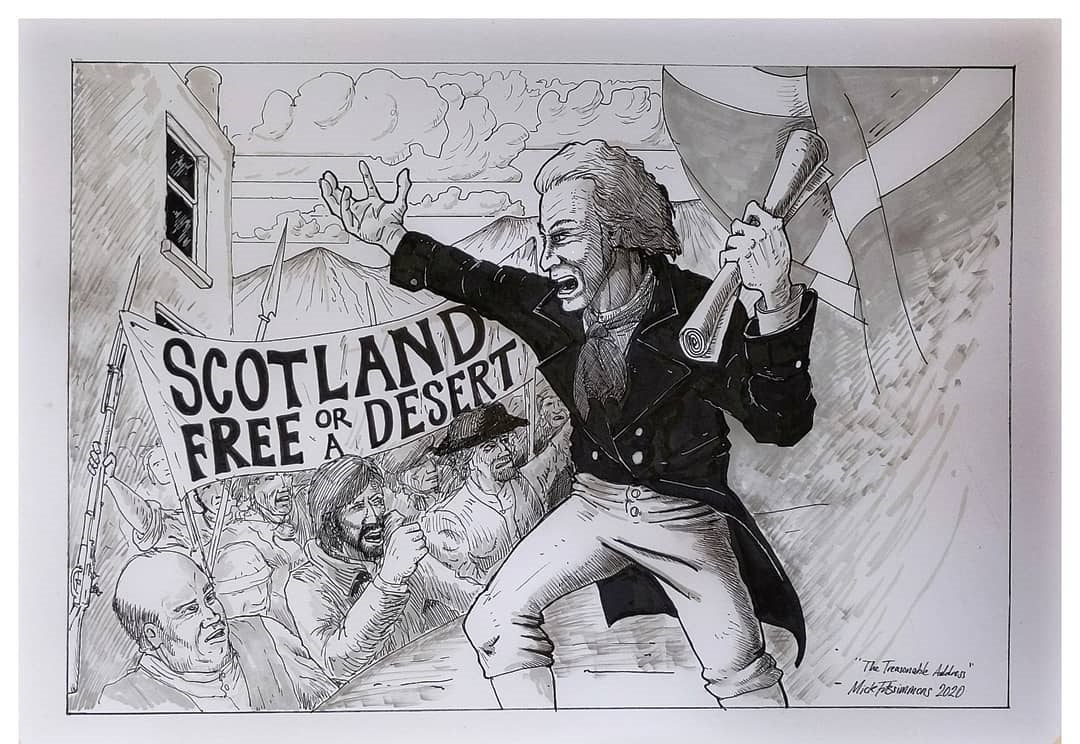

The prevailing sentiment now-a-days with regard to the Radicals of former times, is pity that some of them were made victims by a terror-stricken Government who could not trust the people, and who thought they could stamp out reform as if it had been the rinderpest. Among Liberals, Baird and Hardie are held up to admiration as political martyrs, but it is not unlikely that many of those who shout themselves hoarse, when the political orator refers to the heroes of Bonnymuir, know nothing about who they were or what Bonnymuir had to do with the fight for freedom.

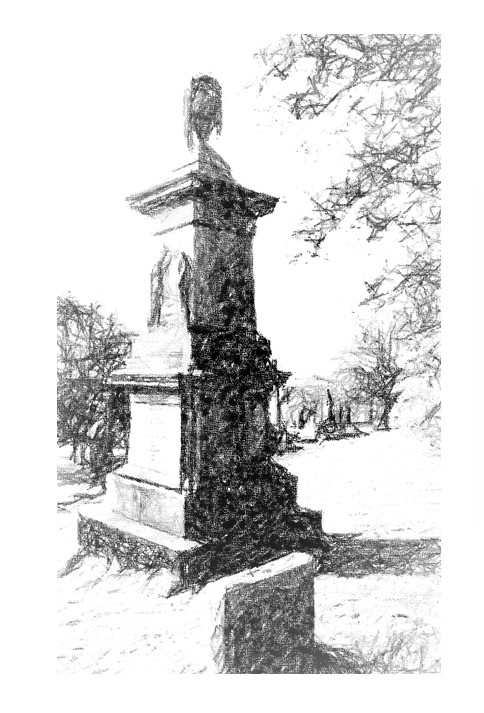

We have no doubt whatever that there are “Sons of the Rock” whose grandfathers may have witnessed the execution of Baird and Hardie in Broad Street, and heard the masked executioner exclaim “This is the head of a traitor!” and whose knowledge of the unfortunate men is limited to their names. It is chiefly as an episode closely connected with local history that we have an interest in the melancholy event of 1820, and seeing that public attention has been again directed to the subject by the proposal brought before the Town Council by Bailie Ronald to mark the ground in Stirling Churchyard, where for a time the remains of the ill-fated radicals reposed, we purpose re-telling the story of Baird and Hardie, purely as an historical incident, adding to the circumstances already published such additional details as we have been able to glean from private sources.

For the proper understanding of our narrative it is necessary to go back to the closing years of the last century, when Europe was in a state of insurrection against authority, and when the flames of the French Revolution had lighted a European War. There were many sympathisers in Scotland with Revolutionary doctrines, and in 1793 four persons Muir, Gerrald, Margarot and Skirving, were transported for sedition, although the means they took to further domestic reform were precisely those which are now open to every party. All they did was to harangue the multitude in favour of Reform, but in the eyes of the Tory Government officials, this was only a little less than treason. “What” exclaimed the Lord Advocate of the day, “what had these transient bodies of weavers and manufacturers in Glasgow, Paisley, Kirkintilloch and other places to do with Reform? The Constitution was matchless, and could not be improved on the face of time.”

The Constitution has been greatly improved since then, but at that period it was dangerous to whisper that it was not perfect. While Muir and his companions were honest, if imprudent Reformers, there were others who were prepared to carry the doctrines of the French Revolution almost as far as the French people did themselves. These extremists did not hesitate to declare that they would like to see a French invasion of Great Britain for the purpose of establishing another Republic. It was not three acres and a cow that would have satisfied the “Black-Nebs”, as they were called. An equal division of property and nothing less was what they demanded, and we have heard in the South stories that might easily be matched in the West and the Midlands, of old weavers and shoemakers who had plans made of their respective burghs and villages, on which they carefully marked off the particular piece of ground they intended for themselves when the Revolution came. It was doubtless one of these “Black-Nebs” who, when asked what was to be done when some men had sold their portion and inequality was again a felt grievance, replied, “Divide again, of course”.

In 1794 was witnessed the awful spectacle of “Revolution eating its own children”, the Reign of Terror ending with the death of Robespierre. The National Convention, defended by Napoleon, was supreme. Previous to this it had set itself up as a Grand Committee of general insurrection for the purpose of overthrowing every existing government in Europe. The Convention had emissaries in Scotland as elsewhere, and numbers of honest well-meaning men who earnestly desired the good of their country, were seduced into projects which were unquestionably of a treasonable character. Among these were Robert Watt and David Downie, both belonging to Edinburgh, one being a wine merchant and the other a goldsmith. As their trial for high treason was the precedent for that of Baird and Hardie in 1820, and as the list of witnesses for the prosecution included a Stirling gentleman whose evidence throws light on the operations of the Republicans in this locality, we may devote the remain part of the present introductory chapter to a sketch of the proceedings in which they were involved.

After the dispersal of the British Convention, a body of which Skirving, one of the four transported for sedition, was secretary, Watt and Downie became members of what was called the Committee of Union, an imitation of the permanent Committee Safety in Paris, and which met in the house of a Mr George Ross in Edinburgh. There was also a sub-committee, an inner ring, of which Watt was secretary and Downie treasurer. At the third meeting of the Committee of Union, Watt submitted a plan of a most extraordinary and daring character. The Lords of Session and Lord Advocate were to be seized, and a fire lighted at the Excise Office so as to attract the soldiers from the Castle. One body of men was to assemble at the Luckenbooths in order to meet the soldiers whilst another assembled at the Weigh-house, so as to enclose the military.

Others were to seize on the Banks and demand the money, which was to be paid over to Commissioners appointed for the purpose. In the event of the attack succeeding, an address to the people was to be issued, ordering all farmers, dealers in corn, hay, &c., not to remove the same under pain of death, and gentlemen not to remove above three miles from their own houses under the like penalty. At the same time an address was to be sent to the King calling upon him to dismiss his Ministers and put an end to the war, otherwise he might abide by the consequences. No time was fixed for the execution of this plot, but to show he was in earnest, Watt went to a smith named Orrock and employed him to make pikes. This man undertook the job, but got frightened when there was a talk of thousands being wanted.

Another smith made 15 pikes to Watt’s order, and was paid 22s 6d for them by Downie. Meanwhile a wright named Fairley, the collector for the Committee of Ways and Means, was dispatched into the country to ascertain what assistance could be depended upon in the event of a rising. Watt wanted him to take some pikes with him to show to the friends of the people, but he objected to this as rather hazardous. He visited Glasgow, Paisley, Kirkintilloch, Kilsyth, Stirling, and other places. He had two papers of instructions, the one to ask the local societies to send their money to Downie, and the other to ask what number of patriots were in these places.

When examined at the trial of Watt, Fairley said – “I went to Stirling, and delivered a copy of these papers to all the people I called on, viz, Dr Forrest in his own house, where there were several others. I had no directions to Dr Forrest, having heard of him I called to ask how the society was flourishing there. I think the name of one person in Forrest’s house was Thomson. They all remained about two hours. I told them the news in Edinburgh, and drew a plan of a pike on Forrest’s table. I then left Stirling and went to Mr M’Cross, a relief minister at St. Ninians”. On being shown a note in his own handwriting, the witness read it as follows: – “S___g, support by money; C__ge not great. S_pp_t, as yet not certain”, which being desired to explain, he interpreted thus – “Stirling – Support by money – Courage not great – Support as yet not certain”.

The witness also said that he showed his commission and instructions to Dr Forrest and at all places he called at. On his subsequent examination at Downie’s trial Fairley gave some additional particulars of his visit to Stirling. The following were the questions and answers –

Q. – On whom did you call at Stirling? –A.– I called on Dr Forrest, with whom I saw a Mr Thomson.

Why did you call on him? Was you acquainted with him? – No, I was not; but had heard in Edinburgh that he was a friend to freedom.

Did you not show him your papers and tell him something about your making pikes in Edinburgh? – Yes, I did, in presence of Mr Thomson and others that were there, and drew a pike on the table, saying, Watt told me they were for self-defence.

What said they was the news at Stirling? – They told me their Societies were not numerous. Were willing to assist us about Edinburgh with money, but could not in anything else.

Where went you from Stirling, and where did you call at next? – I went to St. Ninians, and called on a Mr M’Cross, a Relief minister; and a Mr Brown, a writer.

Dr Forrest was examined as a witness for the prosecution at both trials. The following was his evidence: –

A person named Fairley called on me in May last [Watt’s trial took place in August 1794] telling me he was desired to enquire in what situation the Society was. He gave me three copies of printed bills and a letter, and showed me a paper in which money was requested for Mrs Skirving. He spoke about some collectors, a person to be provided with –.

What was the construction you put upon this blank? – I supposed it should be filled up “arms”.

What did you say to Fairley? – I told him we did not wish to injure anyone, and he should be cautious what he said.

Did Fairley say anything of arms manufacturing in Edinburgh? – He was talking about an invasion; and then made a draught of a halbert, and said he knew a person who could furnish such instruments, who I understood resided in Edinburgh.

When the company supped, what was Fairley’s conversation? Did he say anything of a rising of the people? – He did say something about it; but whether as a thing settled, or what might be done, I am not certain. Some conversation took place of a plan for disarming the solders, which, I understood, was to be done by the persons who sent Fairley west. He spoke of some people in Edinburgh who would repent their conduct and would be imprisoned by the people who sent him. He spoke of Collectors who were to lead and command the people when they should rise. It was said there was to be a Convention similar to the British Convention, which met at Edinburgh. From the conversation I had with Fairley, I gathered there was to be a rising of the people, and seizing of soldiers’ arms.

The crazy plot was easily discovered and Watt and Downie were arrested, tried and convicted of high treason and sentenced to death. The report of the trial from which we have quoted gives an engraving of the pike heads found in the possession of Watt. One is spear-shaped, the length of the spear and socket for pole being 23 inches. The other is a halbert or battle axe, the cross being 8½ inches wide. The whole edges, says the description, are as sharp as a lancet. The same kind of weapons were used at Bonnymuir, and may be seen in the Douglas Room at Stirling Castle.

(To be continued.)