CHAPTER X – 1820

This is the first section of Chapter X of the serialisation, the wording reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, on Tuesday 16th April 1889.

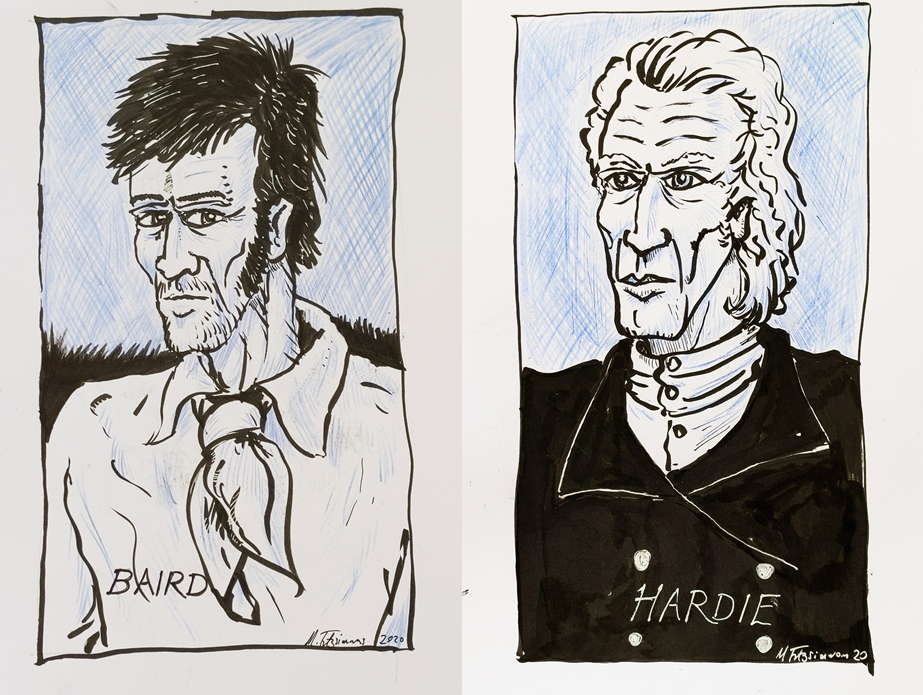

CONTINUATION OF THE EVIDENCE AGAINST HARDIE – THE “BRAVE” YEOMAN, NICOL BAIRD – HARDIE’S OPINION OF THE HERO – MR JEFFREY’S EXORDIUM.

William Grindlay, residing at Bonnymill, deponed to seeing the Radicals pass his house between eight and nine o’clock on the morning of the 5th April. They were going towards Falkirk and Camelon. Some time afterwards he saw smoke at Bonnymuir, and the cavalry pursuing some people. One of the yeomanry had a pitchfork which was standing at the side of witness’s house in the morning and must have been taken away by the Radicals. He now identified it in the box in Court. Cross-examined by Mr Jeffrey – Q. – How do you know that pitchfork to be the same you once had about the house? – A. – I know it perfectly well by the make. Is it of your own making? – No. What is there peculiar about the make of it?

The Lord President – You are treading on dangerous ground, and you need not put this question; it leaves it open to a fair argument for you.

Mr Jeffrey – I am not afraid of it, my lord. How do you know that from any other?

Witness – I know it by the burn upon the shank and the mark of the fork.

The Lord President – I told you you were treading on dangerous ground; there was a fair argument open to you before, and you have gone on and he has told you how he knows it to be his own most conclusively.

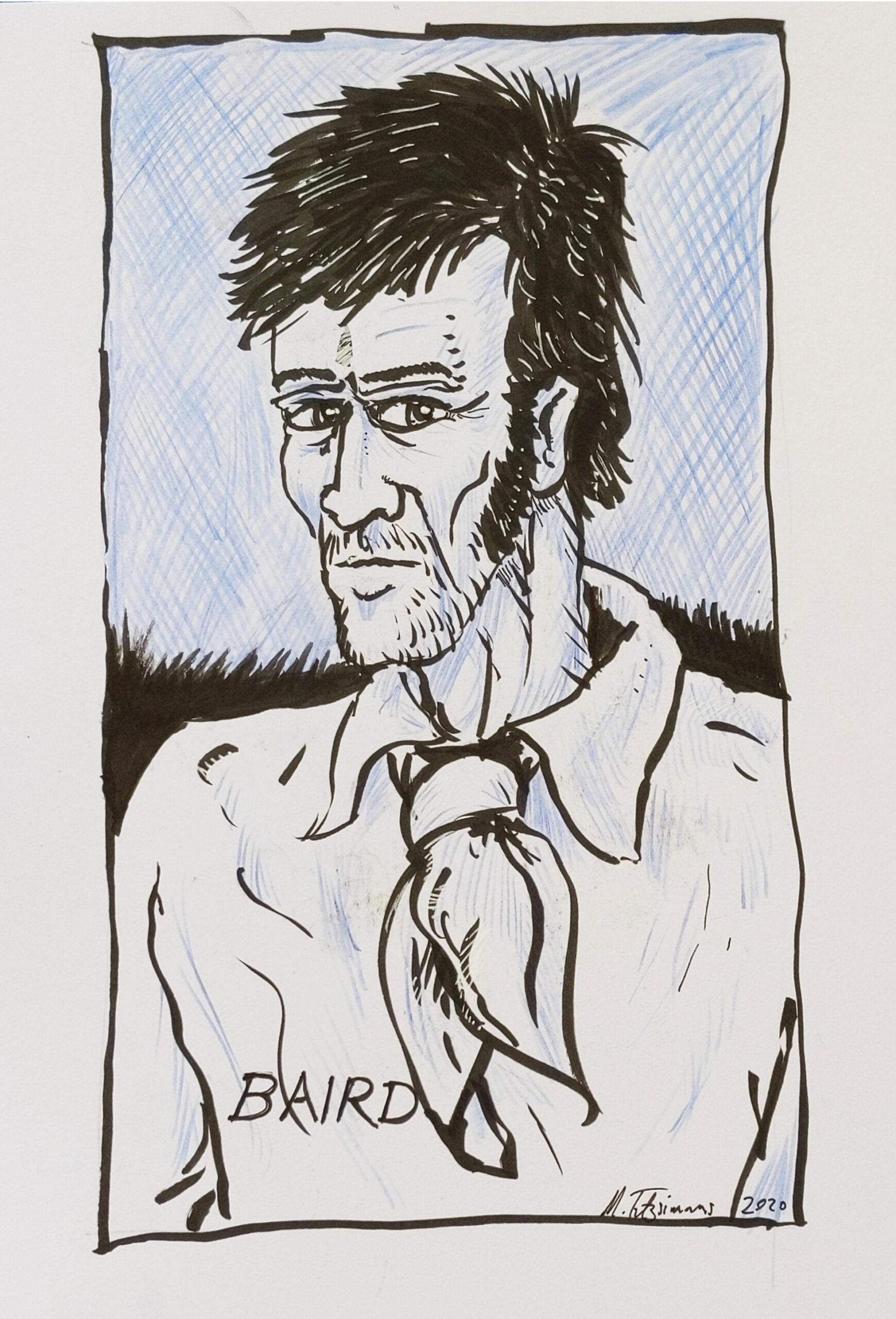

Nicol Hugh Baird, Kelvinhead, the “brave” private in the Falkirk troop of the Stirlingshire yeomanry, deponed to his meeting the Radicals on the road, who obstructed his passage and asked his arms. He drew out his pistol and presented it at them, and then rode off to Kilsyth. He was one of the yeomanry at the “battle” and assisted in taking the prisoners. He thought he saw Hardie at the battle, but he was much altered in appearance. It may be interesting to quote here Hardie’s opinion of this witness, as written in his condemned cell. “The next witness (he says) that I will mention is Mr Nicol Hugh Baird, of the Kilsyth Yeomanry Cavalry, who actually swore that he met ten or twelve of us on the road, and that we demanded his arms, and he in return to our demand, presented his pistol at us, and said that he would give us the contents of it before he would do so.

In the name of common sense what could tempt this coxcomb to swear to such a notorious lies as this to face and frighten ten or twelve armed men. He is worthy of being classed with Sir William Wallace. I am astonished that after such a feat he did not petition the officer of the Hussars to fight the whole of us on the moor himself. But he had done enough for one day. But the truth of the matter is this – We never saw him on the road at all. He had got notice of our approach, and putting more confidence in the swiftness of his horse than his own valour, he either turned or hid himself, until we had passed; and I understand that about twenty people can testify that he did not pass until we were off the road altogether.

How different was the evidence of the Hussar from this Don Quixote, who told the truth and stated our number to be five or six, yet he had more policy than to offer to attack us, and very prudently capitulated with us, and told us after we were taken prisoners, that he thought we were a set of d—– dangerous looking fellows, and yet this imaginary hero, i.e., the yeoman, identified me (the prisoner at the bar) as one of the party. I was more than astonished when I saw him come forward and assert such falsehood, and went immediately and told one of my counsel that it was altogether lies. I saw in the newspapers (when I was in the steamboat going to Edinburgh) an exaggerated account of the battle, stating our number to have been about a hundred; but if there had been that number I am of opinion that I should not be sitting here this day, a solitary prisoner under sentence of death.

But the truth is there were only twenty-four or twenty-six of us, and there were three or four who never came forward at all, so by that means our numbers were reduced to about twenty; and although those men had come forward, they would have been of little service, as I believe they had no arms, for I remember there were two or three without arms, and in all probability it was them that did not come forward. The number of the Hussars and Yeomanry Cavalry were, I think, according to the officer’s own statement, thirty-two; yet they found some difficulty in subduing us. The paper gave an account of us meeting a yeoman on the road, and likewise the hussar, which made me think that the gentleman whom we first met had been him, as he had a tartan on, and saddle bag, and I thought that he might have been armed and in regimentals, although unseen to us, as his tartan cloak was sufficient to conceal them; yet I am certain it was not so, for the gentleman was a lusty, stout man – but the Kilsyth hero was quite the contrary; so I shall now leave this son of Mars”. According to Peter Mackenzie, Mr Nicol Hugh Baird thought fit to decamp from this country soon after the trial was over, and it was hinted that he got a reward from the Government for his evidence against Baird and Hardie.

Sergeant Thomas Cook, the Hussar mentioned by Hardie, deponed that when he met the armed men on the road, they ordered him to halt when he was within twenty yards of them. He did not obey, but came up to them and asked them what they wanted with him, and they replied that they were seeking for their rights. They did not all speak together, but one man said they were seeking for their rights as honest men ought to do. Witness would not pretend to say that Hardie was the spokesman of the party. He (witness) said he was very sorry for their case – he had nothing at all to do with it – and he hoped they would not molest him. One of them said – “I suppose you are an orderly; where are your dispatches?” He replied that he had none, and told them exactly his case, how he was left behind at Stirling and the situation he was placed in. He told them the cause of his being left behind, and they said it was a bad job for him. One wanted to take his arms, but another said “Don’t do it”. Another wanted ammunition, and he said he had none, and they left his arms alone. He told them he was a weaver, and that he had a wife and family of his own, and was very sorry for their situation. They asked him if he could read, and on his replying in the affirmative, one of the men pulled a roll of handbills out of his pocket and gave him one. It was an address to the inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland. They then permitted him to pass, and he rode on to Kilsyth and reported the matter to his superior officer, Lieutenant Hodgson. Witness was afterwards in the engagement at Bonnymuir. Every man that was taken prisoner to Stirling had some arms taken from him of one description or another. In answer to Mr Jeffrey, witness said he could not recognise the person who gave him the paper; he could not say it was Hardie.

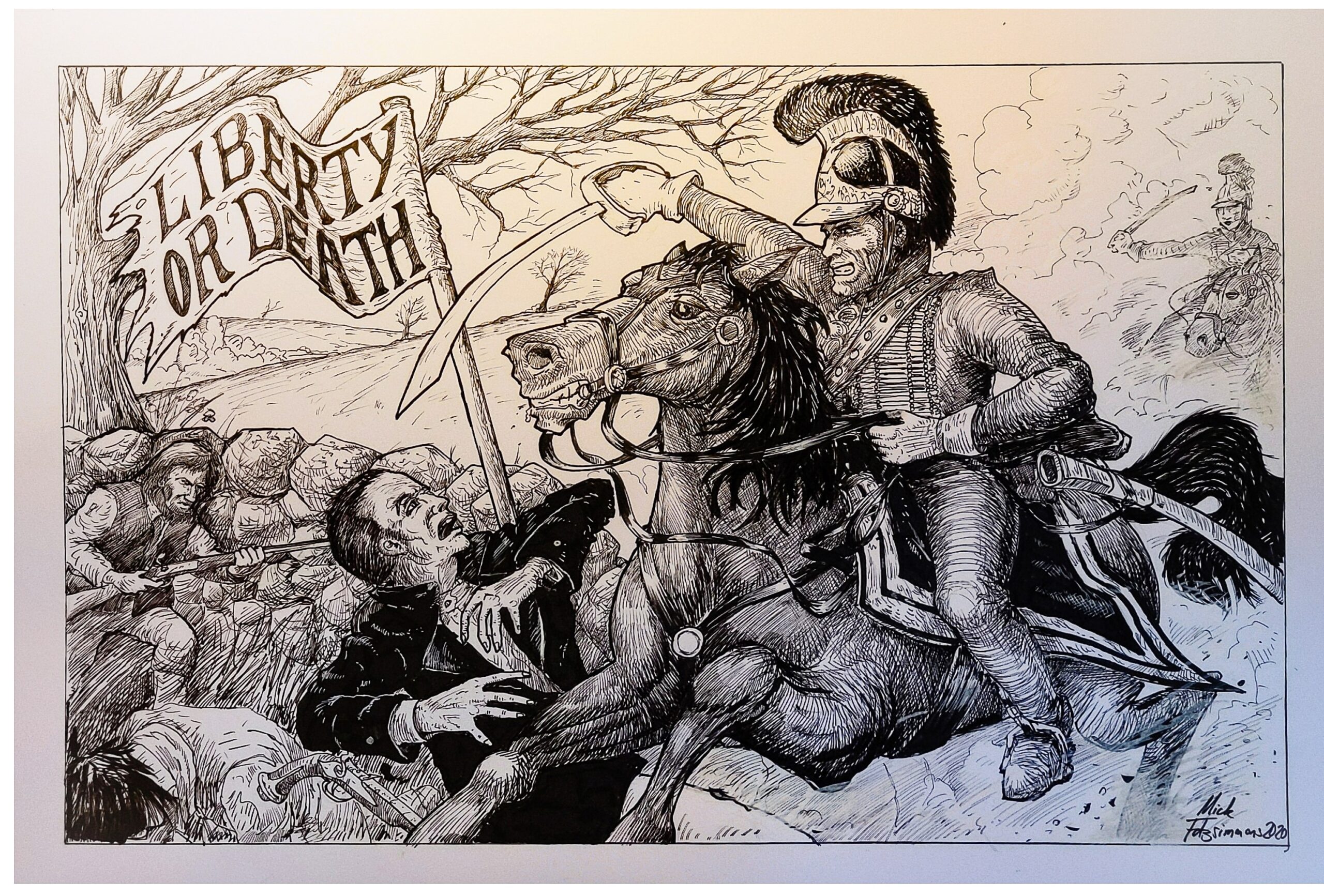

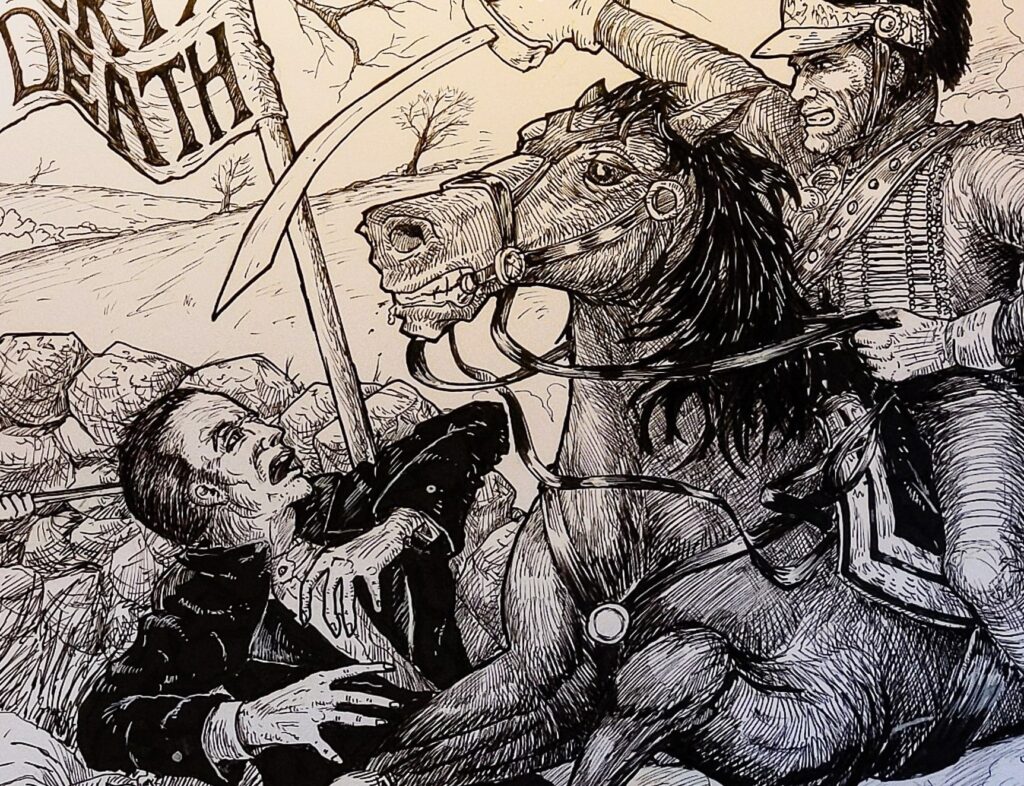

Lieutenant Hodgson described the encounter at Bonnymuir. On getting through the gap in the hedge he presented his pistol at one of the men who appeared to be the ringleader, but it flashed in the pan and did not go off. The prisoner Baird was the man he referred to. His musket had been presented at witness the whole time he was getting round the wall, and he had been told since Baird had pulled the trigger, but he did not know. Witness was afterwards wounded in the hand with a pike, and his horse was shot and died the same night. When the prisoners were being taken to Stirling, Baird and Hardie walked in the rear the greatest part of the way, arm-in-arm. They did not appear to be strangers to each other. In cross-examination by Mr Jeffrey, Lieutenant Hodgson said that when he called out to the Radicals to lay down their arms at Bonnymuir, he thought they said, “We will treat with you”, and it struck him they wanted to make terms with the military.

John James Davidson, lieutenant in the Kilsyth Yeomanry Cavalry, gave similar evidence. He said he knew the man in the black coat (Hardie) and the man in the brown coat (Baird). Hardie was in the front of the party at Bonnymuir, and while Lieut. Hodgson was desiring them to lay down their arms, Baird was presenting a short gun or blunderbuss at him.

Alexander Coutts, gardener at Colzium, a private in the yeomanry, and John Davidson, farmer, Kilsyth, also a member of the corps, told what they saw during and after the skirmish.

(To be continued)