In a recent tweet, Lisa McKenzie made a compelling observation about why working-class communities seem particularly ‘concerned about immigrants and paedophiles’ within their neighbourhoods. As she explains in Getting By, this worry is rooted in the fear of losing control over one’s life, family, and community—a phenomenon familiar to anyone who has experienced the precarities of life at the lower end of the social structure. While her analysis pinpoints this understandable reaction, it also leaves room for a deeper critique of how these anxieties are manipulated, shaped, and redirected by powerful actors to serve broader political ends. This isn’t just fear; it’s fear harnessed as a tool, an ancient yet enduring technology of power, which, as Rene Girard (1986) points out, is as old as civilisation itself.

Historically, scapegoating has been a go-to strategy for the ruling class. Its principles reveal a pattern where blame is strategically displaced onto marginalised groups. The targets vary with the times—currently immigrants and so-called “folk devils” like sex offenders. But the function remains the same: to deflect rage away from the roots of injustice and onto “safe” targets that do not threaten existing power structures.

The scapegoat mechanism has endured for millennia precisely because it yields so many profitable returns for those in power, and because it offers a cathartic release for the working class—a benefit that tabloid-owning billionaires and the professional political class they control, are all too aware of and skilfully exploit. Drawing on insights from various interrelated research projects that we at Erasmus Research are currently involved with, we have identified five key functions of the scapegoat mechanism in modern society.

1. The Detractor Function

By directing the frustrations of the precarious working class downward toward marginalised groups, scapegoating serves to distract from the root causes of their instability. Economic and social precarity—issues fundamentally tied to the erosion of rights, labour protections, and social safety nets—are reframed as consequences of the “outsider” or the “criminal.” This rhetoric pulls focus from systemic inequalities and powerful interests and deflects it onto weaker targets. In this way, the ruling class uses scapegoating to make the powerless fight amongst themselves rather than uniting to confront the forces truly responsible for their precarity.

2. The Restoration Function

Nation-states, facing decreased power to uphold the social contract through welfare provision and equitable policies, attempt to restore legitimacy by creating a shared fear. Through the “dangerous Other,” the state finds a means of appearing indispensable. Only the state, it tells us, can “protect” its citizens from these manufactured threats. This theatre of protection re-establishes the state’s authority not by addressing the people’s needs but by positioning itself as the sole bastion against the dangers it helped construct.

3. The Justification Function

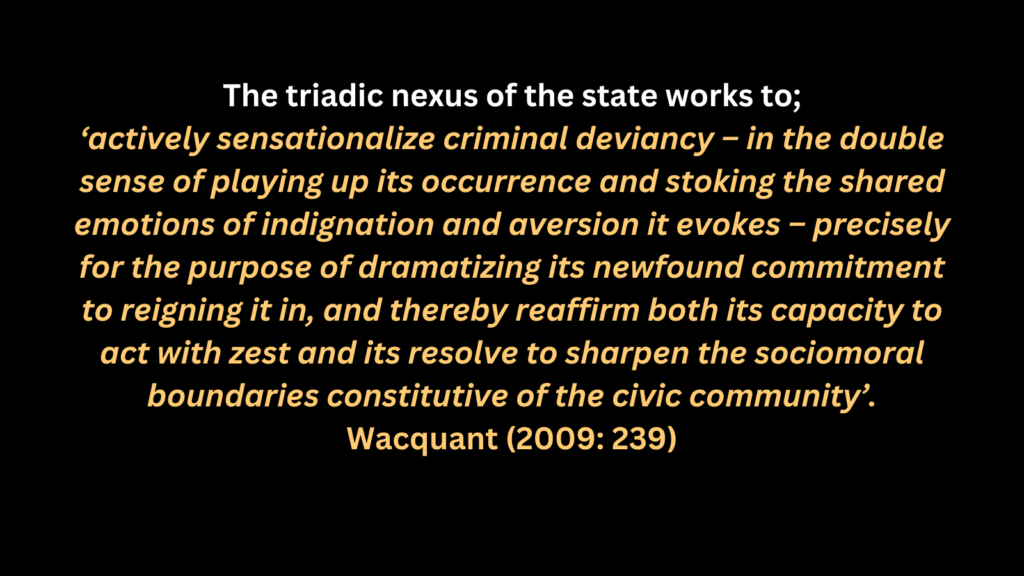

In order to justify encroachments on our freedoms and privacy, the state requires a constant threat. Enter the scapegoat. Fear of the “dangerous Other” justifies a raft of policies that would otherwise be unpalatable—expanded police powers, pervasive surveillance, and an increasingly punitive legal system. As Wacquant noted, the state actively dramatizes criminal deviance, amplifying occurrences of “moral panic” to strengthen sociomoral boundaries and legitimise the steady expansion of its own power.

4. The De-Territorialisation Function

Scapegoating also enables the dismantling of solidarity within traditional communities. As social groups that once provided mutual support—like trade unions and grassroots organisations—are eroded, communities are left vulnerable to division and reorganisation. This creates what Bourdieu described as an “ontological crisis,” a void of identity that is filled with suspicion and anxiety toward new scapegoats. The ruling elite uses this fragmentation to foster competition for resources and status among newly formed social groups, dismantling collective identity and creating communities that are easier to control.

5. The Re-Territorialisation Function

As traditional forms of social protection fade, the state redefines itself through authoritarian measures. With growing inequality and the privatisation of welfare, the state’s legitimacy depends on its ability to instil fear and maintain a monopolistic hold on violence. This function— “re-territorialisation”—requires a constant redrawing of who belongs and who threatens, allowing the state to strengthen its grip through the cultivation of precariousness and the amplification of fear. In this way, the state reshapes society to ensure efficient domination, marking a shift toward what Wacquant called “21st-century fascism,” where the myth of law and order supersedes genuine social welfare.

The Mythology of Law and Order

The amplification of “law and order” is central to this entire mechanism. The political, bureaucratic, and media spheres collaborate to create a shared moral unity through figures of fear—whether immigrants, the poor, or “deviants.” Wacquant aptly describes this triad as a means to reaffirm the state’s resolve to act “with zest” against crime, consolidating its authority by sensationalising deviance. The result? A populace caught between a fading social contract and a growing moral panic, less secure but more reliant on the very state that has stripped away its freedoms.

In sum, the scapegoat is a profound, multifaceted tool in the arsenal of power. By understanding its political functions, we can start to question the narratives we are sold about who is dangerous and why. Recognising scapegoating for what it is—a method of social control—opens the door to challenging this manufactured mythology of fear and reasserting our own power in shaping a society that serves us all, not just those at the top.