This article was first published in October 2016 on the Reimagining Conflict: Pedagogy, Policy and Arts Group Website

This is a link to the original article

On April 14th 2022 the Russian invasion of Ukraine had been relentless for 50 days. The world is struggling to come to grips with, and to respond to the atrocities committed by Russian forces. In the meantime in Ukraine, Russian soldiers are being confronted with extraordinary resistance as Ukrainians have come together to protect their country. The world’s media is watching Ukraine and the public are confronted with a stream of continuous commentary and still and moving images of war, victims, casualties, death, destruction of homes and communities, soldiers, tanks, resistance, and protest.

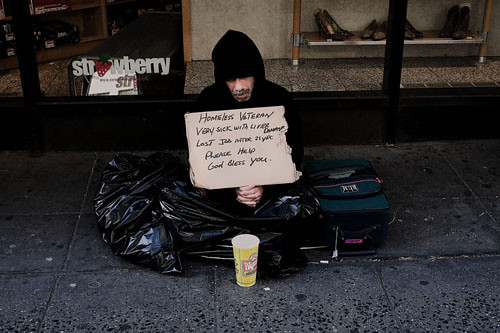

This prompted me to think about not only the people of Ukraine and the Ukrainian and Russian soldiers but also former soldiers who have survived armed conflict. The continuous flow of images has inevitably provoked strong feelings of sympathy and support for Ukraine and this will inevitably have an impact on those who have experienced armed conflict. This has been recognised in that the Veterans Minister Leo Docherty has asked British veterans not to travel to Ukraine and he has asked for military charities to offer their support in this respect (GOV.UK, 2022). In light of this and the power of the image I would like revisit an article that I wrote in 2016 for the Reimagining Conflict: Pedagogy, Policy and Arts Group Website. The article begins below.

Put simply a military ‘veteran’ is someone who has left the military. However, I recognise that the term ‘veteran’ can be problematic in that not all individuals who have left the military define themselves in this way. Many would prefer to be described as ‘ex-military’. For ease of communication I will use the term ‘veteran’ in this paper. The exception to this will be when I use terms as articulated by those being discussed.

The media has and does play a central role in constructions of and responses to veterans. In so doing the visual plays a significant role. Many individuals do not have direct experience of conflict, soldiering, veterans or veteranality. Therefore the media play a pivotal role in public, political and practitioner understanding or misunderstanding of veterans past and present experiences.

One of the areas that myself (Corteen, 2016) and Walklate et al. (2014/2016) have begun to write about is visual victimology. Visual victimology enables individuals and interested groups to explore still and moving visual imagery and accompanying text to see truth claims and myth making in respect of victims and victimisation. I am going to discuss visual representations of veterans including the views of others on the Reimagining Conflict: Pedagogy, Policy and Arts Group website (RCPPAG). First I am going to provide a succinct discussion of the concepts ‘veteranality’ and ‘visual victimology’. Second I will briefly outline the emergence of the visual in criminology that led me to the idea of a visual victimology. Finally drawing on some of the interviews from the RCPPAG website I discuss visual representations of ‘the veteran’ and the role of visual victimology.

‘Veteranality’ is a concept coined by Emma Murray (see Murray, 2016a). The term encapsulates the contemporaneous post-conflict multiple agencies and actors involved in the specific governance of military veterans and surrounding related affairs and activities. Veteranality does not concentrate on the political decision to go to war and nor does it question the military’s integrity. Veteranality as I understand Murray’s explanation of it, is an invitation to try to understand how contemporary society and its institutions constructs veterans post-conflict, and how subsequently the public, and the political responds to veterans. Visual victimology can be an important conceptual lens in this respect – in that it encourages a critical analysis of media images of veterans as victimisers and victims.

I noted in 2016 that visual victimology draws attention to the visualisation of real and/or imagined victims and victimisation. It recognises and acknowledges that representations of victims “entail more than those resultant from crime as encompassed in the criminal law” (Corteen, 2016, p. 268). Visual victimology is an invitation to and an analytical tool for the exploration of victims of crime and zemiological victims – that is victims of social harm. Walklate et al. (2014/2016) draw attention to role of visual victimology in revealing the power of the image in the legitimation and delegitmation of victims. Similarly I have suggested that visual victimology enables an investigation of the manner in which victims of crime and social harm are “articulated, rearticulated and dearticulated” (Corteen, 2016, p. 268). Visual victimology may therefore be one conceptual tool to aid an understanding of how the media informs and/or deforms society’s understanding of war, conflict, veterans and veteranality. Visual representations in the media especially news media may be selective or even skewed. Yet, the use of the visual through aesthetics and art may produce and bring to the fore various truths, alternative images and marginal narratives of veterans experiences of war, conflict and transition. I will come back to this.

First I would like to touch on the issue of representations and to briefly trace key developments in the study of representations, visual and otherwise, of crime, agents of social control, and victims within the disciplines of criminology and victimology. Representations can be factual, fictional or factional. They can take the form of the visual, audio or text. Central to representations, visual and otherwise is the media, especially news media in all its manifestations. McQuail (2010) rightly discusses the heterogeneity of the media in that there is no one format, purpose or agenda. Rather the media is a modern, global, developing and growing, multi-faceted industry that is complex, contradictory and contested. There are disputes and disagreements regarding intended and received media messages, visual or otherwise. There is, however, some agreement. For example, theorists such as Cavender, (2004), Marsh and Melville, (2009); and Jewkes, (2015) contend that media is a significant communicative tool that plays an increasing important function in contemporary societies. This is especially so for news media. Media including news media seeks to entertain, educate and make profits. It plays an important role in ideological struggles and setting agendas. Cavender (2004, p. 336) comments that the media “help define what we think about, what we see as problems and the solutions we consider”.

Contemporary media inherently relies on the visual. The visual has always been an important and dynamic factor in how individuals make sense of themselves, each other, and society. Thus it is important to understand the manner in which the visual is used today. For example, at the level of visual popular culture what do we see, how do we see it, who is doing the showing and telling, what goes on behind the scenes and what is it that we are not being shown? Where is the scope for resistance?

In 1998 Rawlings discussed the idea of ‘popular criminology’ – Rafter built on this in 2007. Both Rawlings and Rafter recognise the worthiness of studying the popularity and impact of factual and fictional accounts and representations of crime. Haywood further developed criminological concern with visual representations in 2009 when he called for a ‘visual criminology’. This was in order to encourage criminologists to recognise and to try and understand the power and influence of visual culture in an increasing 24/7 mediascape. The development of an increased interest in mediascape and visual representations of criminal matters has been described by Carrabine in 2012 as the “visual turn in criminology” (p. 464). This is not to say that there has been a visual turn per se. As I noted earlier the significance of the visual is not new – the visual has always played a pivotal role in meaning making and sense-making. For example, Walklate et al. (2014/2016, p. 266) note how since the nineteenth century “photography has been an important source of social narrative”. Also Brad Evans on this website (2016) encapsulates the longevity of the visual when he asserts, “[h]uman life has always been driven by the power of image and imagination.”

However, as Walklate et al. (2014/2016, p. 266) rightly state, “… it is important to embrace the fact that – unlike pictures kept in the traditional photograph album – digital images do not fade, possess electronic mobility, and facilitate instantaneous exchange”. Thus in a context of 24/7 mediascape and the visual digital age, the visual turn in criminology reflects a turn towards the serious and sophisticated study of the visual in the discipline of criminology. This includes the rigorous study of popular representations of crime and of criminal justice including how criminal justice practitioners employ the visual in their policies and practices.

Within criminology and criminal justice, victims are more often than not neglected or an afterthought. This appears to be the case with regard to the emerging interest in, and discussions of, visual representations. This is a somewhat curious position given that “[w]here there is crime – real or imagined there is a victim – real or imagined or a combination of both” (Corteen, 2016, pp. 266-67). This prompted me to ask “is there a visual turn regarding victimology and if so is a visual victimology necessitated and desirable?” (Corteen, 2016, p. 266).

Walklate and Mythen (2008) and others, including Walklate et al. (2014/2016) have highlighted that new media technologies have resulted in a greater public awareness of victims and victimisation. When using the term ‘visual victimology’ I too wanted to acknowledge that “as visual representations of crime have been increasing, so too have images of victims, both fictitious and real” (p. 268). But how informed or deformed is this awareness and what are the consequences for those being visualised and those rendered invisible?

As primary and secondary victims, nationally and internationally “have become a media staple – whatever its format” (Corteen, 2016, p. 268) then victimology needs to pay attention to this development. Victimologists should seek to understand the role of power and powerlessness in the victims who are popularly and culturally visible and thus articulated and rearticulated and the victims that are invisible and dearticulated. Walklate et al’s (2011) exploration of a cultural victimology in 2011 is a welcome development in this respect. So too is Walklate et al’s (2014/2016) use of the visual victimological lens in their exploration of visual representations of trauma, suffering and justice in photographs of terrorist attacks. My discussion a visual victimology reinforces their work and the desire for the conversation to be continued (Corteen, 2016).

So at the heart of visual victimology is the recognition of the increasing popular and cultural significance of visual constructions, reconstructions and visual imaginings of victims and victimisation and its academic investigation. Be this via cultural, radical and critical victimology or a victimological hybrid.

War, conflict, soldiering, and transition from military life to civic life entail individual and collective human suffering. Human suffering and its victims at home and abroad has itself become a central target and feature of visual representations. For example images of victims of human suffering feature in highly popular charity shows such as Children in Need, Live Aid and Comic Relief (Höijer, 2004). Höijer (2004) comments on how “pictures of distant victims of civil wars, genocide, massacres and other violences against civil populations” play “a basic role in giving publicity to human suffering” (p. 513). Höijer continues stating that visual displays of “distant suffering have become part of ordinary citizens’ perceptions of conflicts and crises in the world” (p. 514). Walklate et al. reiterate this (2014/16) in their discussion of the pervasive use of imagery in conveying individual and collective experiences of victimisation as a result of terrorist attacks.

Furthermore with regard to the coverage of war, BBC war reporter Martin Bell noted the shift in focus from the visualisation of “military aspects, such as strategies and weapons systems” to that of “the people who provoke them, the people who fight them and the people who suffer from them” (cited in Höijer, 2004, pp. 515-16). But what of veterans of legal and illegal wars and conflicts who have imposed suffering and who have and are suffering? What may be the role of visual victimology in understanding the visual victims and victimisation in visual conflict, visual soldiering and the visual veteran? Also what may be the role of visual victimology in visualising the invisible veteran’s individual and shared pre-conflict, conflict, and post-conflict experiences?

Drawing on some of the interviews which have contributed to the RCPPAG website I am going to pull together the ways that military veterans have been made visual – for worse and for better. It is established in many of the interviews that experiences of conflict and the occupational culture of soldiering mean that the transition from military life to civic life is ontologically difficult. They also establish that the mainstream representation or misrepresentation of veterans is selective containing repeated, continuous tropes and stock images.

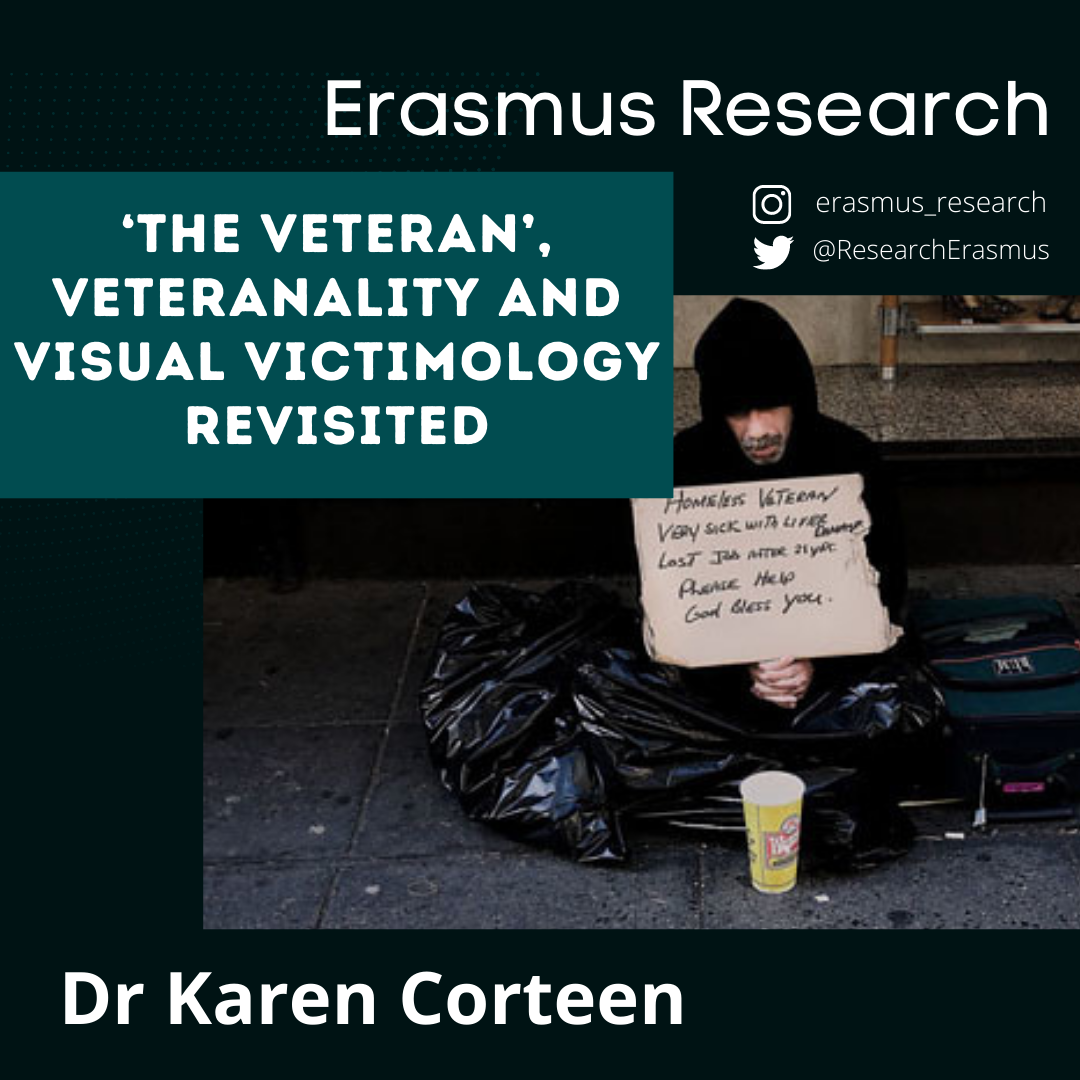

Repeated tropes and stock images include the representation of veterans as that of a heroic or tragic figure – a victim – or that of a deviant or violent criminal. As Emily Gee (2016) rightly points out the prevalent visual image of the veteran is that of an elderly (white) male paying their respects at Remembrance Sunday. Put the word ‘veteran’ into Google Images and this is the first image that you will see, followed by hundreds like it. Whilst there may be a smirch of truth in these representations they most definitely do not convey the lived material corporeal realities and truths of the majority of contemporary veterans – post Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts.

Jay (2016) an ex-military soldier highlights how ex-military personnel have been detrimentally depicted as ‘mad’, ‘bad’ or ‘sad’ and how such a response acts as a barrier to understanding the ontological transition from life as a soldier, and a trained killer, in the collective and contained world of the military, to that of a disconnected world of the individual, private self. Also for Jay whilst ex-military individuals are due respect for the difficult job that they have undertaken, the heroisation of the commissioners of violence and killing is problematic.

For Hannah Wilkinson (2016) the dominant media representation of veterans as veterans, and as victims or offenders is problematic. This is because it invisiblises and silences an unidentifiable group of ex-military personnel who do not identify as veteran and who may also be experiencing a lack of civilian identity. Ontologically located somewhere in between a military identity and a civic identity such veterans exclude themselves from networks and support aimed at veterans.

Wilkinson innovatively uses the visual in the form of photographs to access these dearticulated and unheard voices. Via the visual her participants are able to articulate the trauma of war and military service. In so doing they are able to shed light on the victimisation they have endured as an endemic part of war and conflict. Wilkinson explores the experiences of ex-military personnel through the theoretical or conceptual lens of ‘combat capital’ – a term coined by her. In doing so she demonstrates how academic research and theorisation together with the voices of returning soldiers and speaking on their behalf can enable a more sophisticated way of understanding ex-military personnel.

Sandra Walklate (2016) discusses how soldiers returning from war have always been problematic due to the experiences of war. Drawing on critical victimology she questions why contemporarily there is the framing of the soldier as deviant and she highlights the difficulties in framing the soldier and veteran soldier as victim. However, like Wilkinson (2016), Walklate’s work also highlights how academic theorisation can frame soldiers and veterans as victims and ordinary men rather than offenders. Thus, the mainstream theorisation of military veterans as ‘bad’ in that they are deviant, or ‘sad’ in that they are tragic individual victims for whom no one takes responsibility can be challenged.

Putting soldiers in the frame as victims of scapegoating in order to obscure the perpetration of atrocities on the part of the state tells a different truth in terms of soldier’s experiences during war and conflict and post war and conflict. Significantly it spotlights the legal, illegal, ‘lawful but awful’ and harmful actions on the part of states and state actors – including against soldiers and veterans. Murray (2016b) in discussing the work of McGarry and Walklate (2011, see Murray, 2016b) sums up this position well when she states, “[w]hile framing the soldier as a victim is not without its challenges, it directs a critical criminological and victimological understanding of the effects of war and an all too often obscured culpability” (p. 221)

Fact’s (2016) Veterans in Practice arts project uses the visual to construct alternative images of military veterans. For example using animation and music in a co-production between veterans and artists they have produced a film that tells the shared and individual stories of veteran’s transition (or lack of) from military to civic life. Jay’s involvement in the visual in the form of art is a way for him and others (participants and audiences) to understand the trajectory of the self before military life, during military life and post military life.

In the North West (of England) alone there are an estimated 500,000 military veterans and this figure is predicted to be on the increase (Fact, 2016). It is important that they and other veterans are represented accurately. Academic research, the interviews with individuals within and without academia and art projects that involve veterans such as that featured on this website, demonstrate that popular and cultural representations and visualisation of veterans has been and can be problematic. They also illustrate pedagogic and artistic resistance to mainstream misrepresentations together with the production of individual and shared truths of war, conflict, transitional experiences and veteranality.

Visual victimology is a conceptual lens that can be employed to challenge the use of imagery and text in truth claims about veterans and veteranality. This includes recognition and critical contextual analysis of multiple mainstream and marginal imagery, narratives and testimonies of trauma, survival, resilience, and resistance. Critically unpacking the complexities of visual representations of human suffering as a result of war and conflict is necessary in order for public, political and institutional responses to returning soldiers to be better informed and for best polices and practices to be devised. The Reimagining Conflict: Pedagogy, Policy and Arts Group website and resources is a clear illustration of how veterans, academics, and artists and art, independently and together have a role to play in the deconstruction, reconstruction and reimagining of the veteran and their shared and individual experiences.

Afterword

In 2019 International Alert published a policy brief titled What’s next for veterans in Ukraine? (International Alert, 2019). Its aim was to examine “the role of gender norms … in shaping and reshaping integration experiences of female and male former combatants – professional soldiers, conscripts and volunteers – who fought in Eastern Ukraine between 2014 and 2017” (International Alert, 2019, p. 1). This conflict was the first armed conflict on Ukrainian territory since the mid-20th century. Today’s ongoing armed conflict in Ukraine will sadly result in yet more veterans in both Ukraine and Russia and possibly elsewhere. Therefore, it remains vital once the conflict is over that returning soldiers are responded to in a manner that is informed by the best policies and practices. Visual victimology continues to play a role in that a critical unpacking of images of human suffering as a result of war and conflict can aid an understanding of returning soldiers and their families experiences together with the experiences of those impacted on by conflict including current veterans who may be vicariously harmed.

Bibliography

The full list of references with links to sources can be found in the original article here