This is the second section of Chapter IV of the serialisation, the wording reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, on Tuesday 5th March 1889.

We must return, however, to the Address, in order to trace the steps of the Government spies who were at the bottom of the conspiracy. About ten days before it was published a meeting of Radical delegates assembled in the house of a vintner in the Gallowgate on the special invitation of one John King, a warper or weaver, who was elected chairman, and submitted to the meeting communications which he said he had received from England. He then said it would be necessary for him to leave the meeting before nine o’clock. Suspecting treachery, a Paisley delegate objected to anyone leaving the room till the meeting broke up, but King managed to slip out for a moment or two, and after his return, just about nine o’clock, Bailie Hunter, and a strong body of police and military, entered the room and made the whole party prisoners.

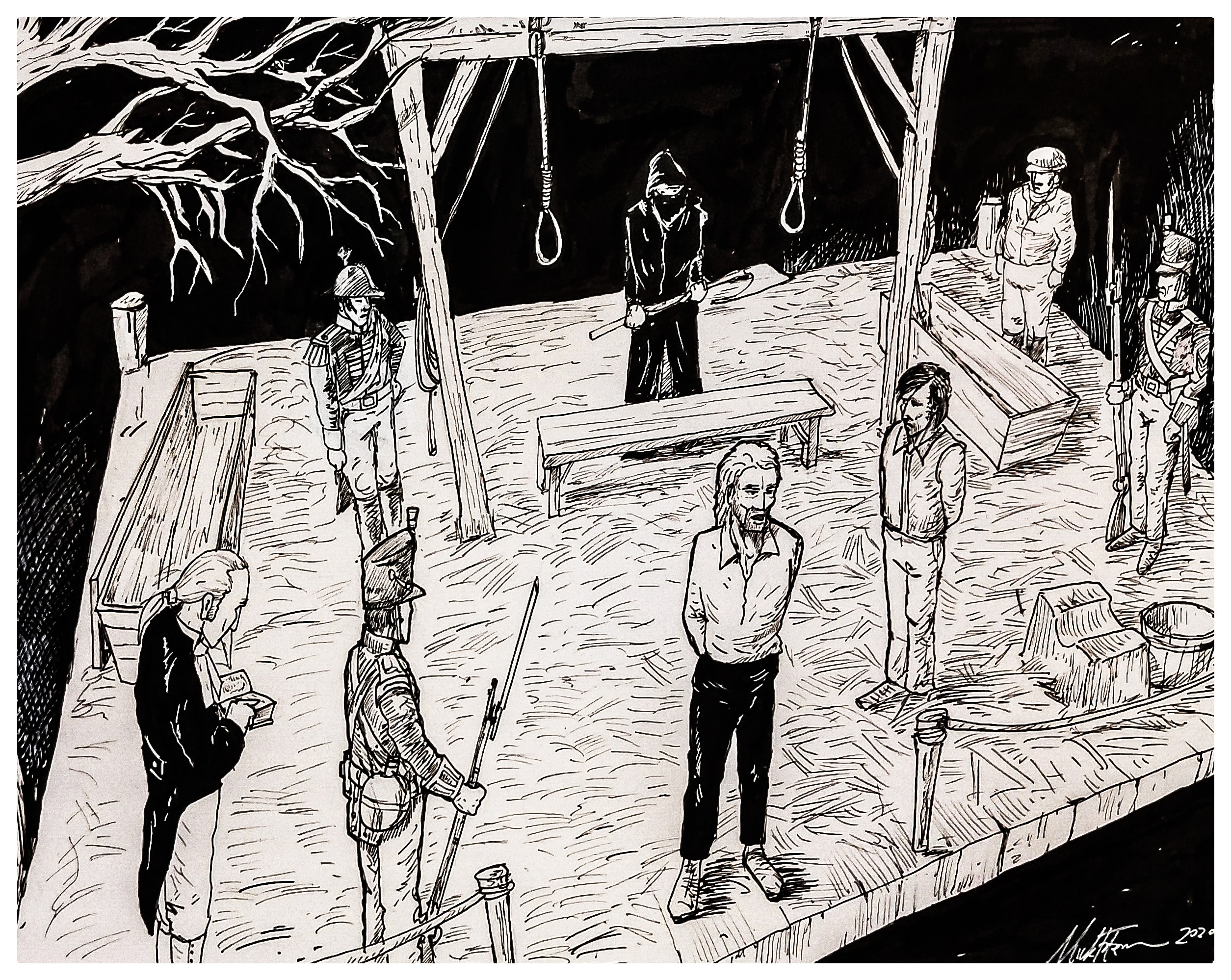

It was fortunate that some of the papers which King wished the meeting to adopt had been burned, or the delegates would have found themselves in a serious position. As it was, they were taken to prison, and, with the exception of King, were detained there until after the execution of Baird and Hardie, without any charge being proved against them. The early liberation of King, who was the principal offender, can only be explained on the hypothesis that he was a Government spy, and was required for the execrable part he afterwards played in leading Baird and Hardie to destruction. The delegates were the dupes of others who, like Richmond, contrived to keep themselves behind the scene.

“The Committee of Organisation for forming a Provisional Government”, from whom the Treasonable Address emanated, was, as Peter Mackenzie says, a mere phantom, or if it had any existence at all, the persons composing it were the hired spies or tools of the Government. We have already seen how the Address reached the hands of the printer, namely, by a spy named Lees, and it is amusing to find that on the 8th April, three days after the “Battle of Bonnymuir”, a Royal Proclamation was issued, offering a reward of £500 for information as to the authors and printers of the Address.

It is probable the Government knew all about it, and were cognisant of the fact that Fulton, the printer, had been packed off to America lest he should make any awkward revelations. The “copy” for the Address, delivered secretly to Fulton by Lees, was written by John Anderson, the son of a Glasgow writer, from a printed copy furnished to him by Duncan Turner, who was undoubtedly an emissary, or spy of the Government. Fulton was an apprentice with a Mr Mackenzie, and he printed the Address without the knowledge of his master. The typesetting was completed before midnight on the Friday, and the greater part of the copies were thrown off before five o’clock in the morning.

The first parcel was delivered at the house of a man named Craig, another of the gang of spies, and the printing was resumed the same night, and before twelve o’clock Lees received the balance from Fulton in the Globe Tavern. Craig was present, and the pair carried the parcel to King’s house. Here King was found in company with a number of men, who were arranging pikes and gunpowder, while King and his wife were plying them with whisky and talking in the most confident strains of the great and glorious doings that were about to take place. King’s house was, in fact, the head-quarters of the Revolutionary movement. Yet he always managed to escape, which is a clear evidence that he was acting under the instructions of others whose aim and object was to get the Radicals to commit themselves by some overt act of rebellion.

The “Treasonable Address” was piled up in quantities in King’s house. He himself talked in the most significant manner to the delegates present of the important communications he had just had with the Provincial Government, who, he said, were all men of rank and talent – that Kinloch of Kinloch was returning from France, whither he had fled for denouncing the Manchester massacre, and that Marshal Macdonald was also coming from France to their assistance with a body of troops, and a large quantity of gold, &c. Turner, the spy, carried away a quantity of the Addresses for the purpose of putting them up through the city, and next day they appeared on the walls.

It is at this stage that Andrew Hardie first appears upon the scene. He was a weaver by trade, a native of Glasgow, twenty-six years of age, and living with his mother in the High Street. He was a steady respectable man, and was engaged to be married to a young girl named Margaret M’Keigh. Like the majority of the weavers, he took an interest in politics, and was a strong Radical, universal suffrage and annual Parliaments being the two points he held of most importance. Not very extravagant views, as we think now-a-days, but at that time the motto of the extreme Radical Reformers. On Sunday morning, 2nd April, Hardie left his mother’s house, and at the corner of Duke Street, which branches off High Street, his attention was attracted to a copy of the “Treasonable Address”, which was posted up on a watch-box. Several individuals were standing reading it, and Hardie joined the group and began to read it aloud. Unfortunately for him, there was another Hardie in the vicinity – a Mr James Hardie, J.P., who lived in Duke Street, and who, strangely enough, thought it his duty to go abroad early in the morning for the purpose of removing the inflammatory placards from the walls.

How he came to know there was such a thing in existence, has never been explained, and it is supposed that as he was one of the local authorities who afterwards made themselves prominent in the business, he knew very well that the police had received orders not to hinder anyone from sticking up bills during the Saturday night, and that he went out at eight o’clock on Sunday morning in the full knowledge that the “Treasonable Address” would be found on the walls of the city. At any rate, he turned up while Andrew Hardie was reading the placard, and according to his own statement, he forced through the crowd for the purpose of pulling it down, but was prevented by Hardie, who jostled him off the pavement and seized him by the collar. He (Mr Hardie, J.P.) said it was a most improper address to remain there, and insisted on taking it down, telling the crowd that he was a magistrate.

Hardie asked him where was his authority, and told him that before he would permit him to take down the paper he would part with the last drop of his blood. Hardie, J.P., then made another attempt to get at the watch-box, but again failed, and eventually walked away, and a few minutes afterwards removed one of the Addresses from a pump-well, which copy he carefully preserved and had in his pocket when he was examined as a witness against Hardie.

The latter wrote an account of the whole affair while he was lying in Stirling Castle under sentence of death, and his version of the incident is as follows:- “I do not deny preventing him taking down the bill and asking his authority for doing so; neither shall I mention the abusive language he gave to me, nor what I said to him. But as I have a good and just God to answer, and to whom I must give an account of all my actions in a very short time, I hope you will form a more favourable opinion of me than to think I would tell you any lies. He said that I seized him by the collar and drew him off the pavement twice, but it is very strange that I mind all that passed, and cannot charge my memory with doing so”.

It is said that after Hardie had been found guilty, an altercation took place between Mr Hardie, J.P., and a Mr Thomas Hopkirk in one of the inns of Stirling, in presence of two or three persons, and that Hopkirk directly taxed Hardie with having strained his evidence to an unwarrantable extent against his poor namesake. Hardie hung his head, and did not venture to deny the charge. The zealous J.P. was afterwards appointed superintendent of the Glasgow Police, an application to the Home Secretary for an allowance as a stipendiary magistrate having been refused. In our next chapter will be given an account of the Battle of Bonnymuir.

(To be continued.)