This is the second section of Chapter II of the serialisation reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, word for word, on Tuesday 19th February 1889.

… continued

The year 1812 witnessed a revival of the demands for Reform, which grew louder as the distress and discontent of the people increased, and once more a Tory Government, by its obstinacy in refusing to listen to any proposal, however reasonable, provoked the recurrence of the scenes of 1793. The first overt movement made by the Radicals was to hold a great public meeting in Glasgow in October 1816, at which resolutions were passed in favour of addressing the Prince Regent “for a redress of grievances in the Commons House of Parliament”. This meeting was held in defiance of the local authorities, who threatened the Reformers with the military if they dared to go to Glasgow Green.

The Magistrates also prevented them getting the Trades Hall to meet in, and after they secured the stable-yard of the Eagle Inn in Maxwell Street, the landlord was intimidated into refusing them the use of his premises. “Gotham in Alarm” was the title of one of the severe squibs that appeared against the Magistrates, and Sandy Rodger wrote a satirical address to the Radicals in which the powers that were, were represented as saying –

“We’ve walth o’ sodgers in the toun

To keep sic ragamuffins doun;

And gin ye dinna settle soon,

By a’that’s guid!

We’ll gar the comman sewers rin

Wi’ you base bluid!

Tak, therefore, this kind admonition:

Recant, repent, be a’ submission;

And, as a proof that your contrition

Is frae the heart.

In Gude’s name burn that vile petition

Before ye part”.

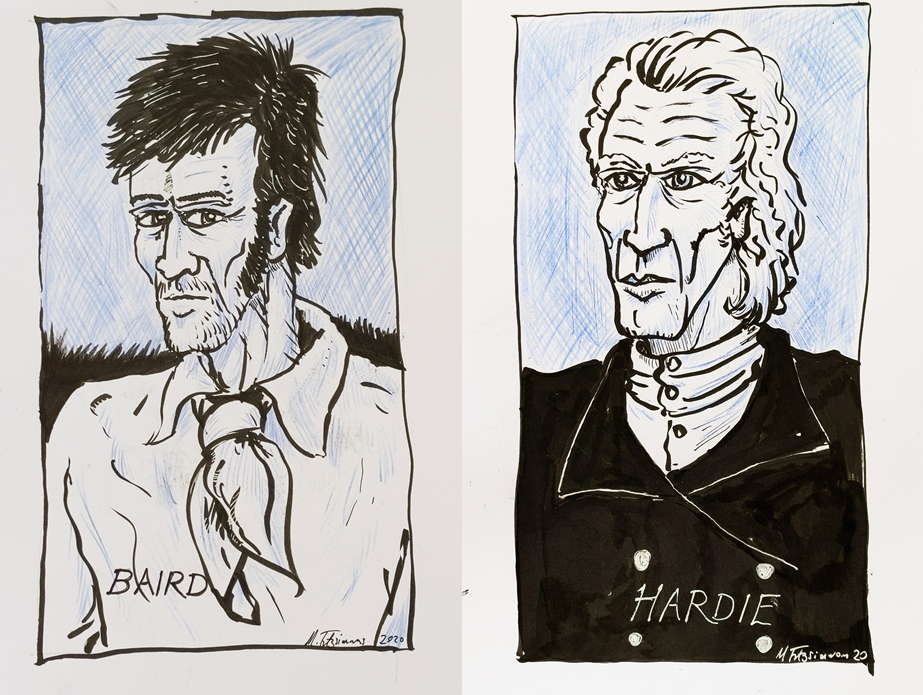

The promoters of the meeting found a friend in James Turner, a tobacconist, who was afterwards associated, as we will find, with the monument to Baird and Hardie. This courageous Reformer, at some risk to himself – he was actually committed to prison on a charge of high treason – gave the Radicals the use of one of his fields at Thrushgrove, a name which, according to Peter Mackenzie, charmed the ears of Glasgow Reformers for many a day. The field has long been covered over with dwelling-houses. The meeting was attended by upwards of 40,000 persons, and was conducted with the utmost order and decorum, probably because it was known the military had been served with twenty rounds of ball cartridge, so as to be ready for any emergency.

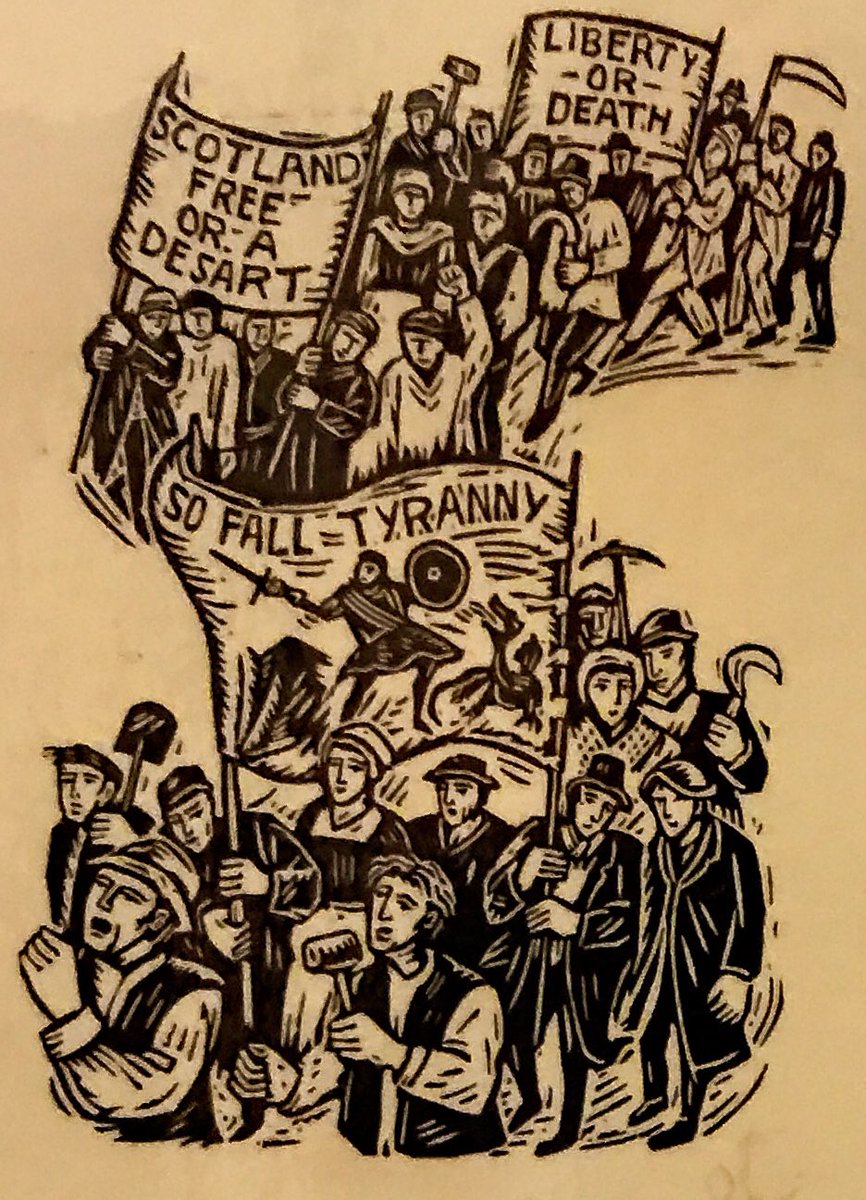

“Radical Reform” then became the cry throughout the kingdom. There were many great meetings in the open air, “violent petitions, crazy projects, new restrictive laws on the expression of opinions, the burning of machinery, outrageous loyalty, popular excesses, lecturing demagogues, wild theories of government, universal excitement”. The Habeus Corpus Act was suspended, so that the Government might have freedom to strike at the Radicals, and an odious system of espionage was adopted by which many respectable persons were brought into trouble, and through which Baird and Hardie were led into a trap which cost them their lives.

One of the most accomplished of the vile set of spies employed by the Government was a man named Alexander Richmond, originally a Pollokshaws weaver, but who, by the mistaken kindness of some of the Whig leaders, was enabled to start in Glasgow as a weaving manufacturer. When Mr Kirkman Finlay, M.P. for Glasgow, took upon himself the task of “detecting” the principal Radicals in the city and reporting their proceedings to Lord Sidmouth, Secretary of State, it was Richmond he sent for and appointed as his confidential agent, the tool and spy of the Government, whose services were to be paid out of the “secret service” money. It manifestly became necessary for Richmond to discover something in order to earn his wages, and he soon reported to Mr Finlay that the Glasgow weavers were taking secret oaths to do what in them lay to overthrow the Government by physical force on the pretext of Reform. The spy was able, he said, to produce a copy of one of these oaths, which he had procured at great personal risk and expense. It was in the following terms :-

“In the awful presence of God, I _______ ______ do solemnly swear that I will persevere in my endeavouring to form a Brotherhood of affection amongst Britons of every description who are considered worthy of confidence: and that I will persevere in my endeavours to obtain for all the people in Great Britain and Ireland, not disqualified by crimes or insanity, the elective franchise at the age of twenty-one, with free and equal representation and annual Parliaments, and that I will support the same to the extent of my power, either by moral or physical strength or force, as the case may require. And I do further swear that neither hopes, fears, rewards, or punishments shall induce me to inform on, or give evidence against, any member or members, collectively or individually, for any act or expression done or made, in or out, in this or similar societies, under the punishment of death, to be inflicted on me by any member or members of such societies. So help me God, and keep me steadfast”.

In comparison with oaths which have seen the light recently in connection with Ireland, the above seems a very tame affair, but it was held, and rightly held, to be a treasonable oath, and prosecutions for subscribing it followed its alleged discovery. We say “alleged”, because in point of fact the oath was the invention of the scoundrel spy Richmond, who got a number of weavers to sign it on the representation that it was merely a declaration in favour of reform, and was quite harmless. To the same cunning forger was due the “treasonable proclamation” which precipitated the battle of Bonnymuir, and brought Baird and Hardie to the scaffold. This will be made clear when we come to that period. We are still at 1817, three years before the “spy system” reached its fatal climax. The first copy of the oath produced by Richmond was signed by a simple weaver, named Andrew M’Kinlay, and this document was sent to Lord Sidmouth, who at once summoned a Cabinet Council to consider it, and in a few hours it was read to both Houses of Parliament, causing great sensation and alarm. The Lord Advocate was instantly sent down to Scotland with instructions to put the criminal law into execution, with the utmost rigour, against the “traitors” of Glasgow.

(To be continued.)