CHAPTER XV

This is Chapter XV of the serialisation, the wording reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, on Tuesday 21st May 1889.

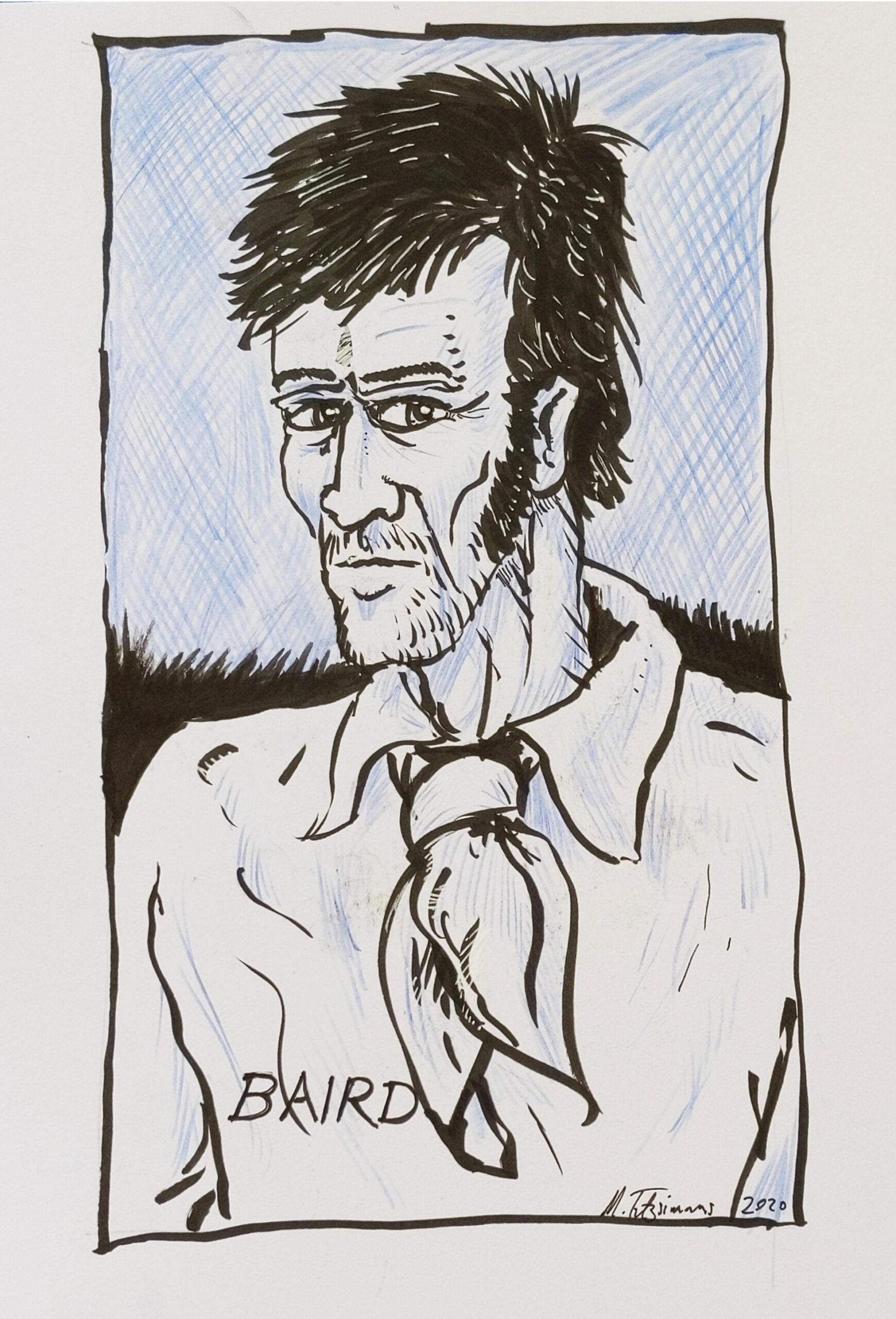

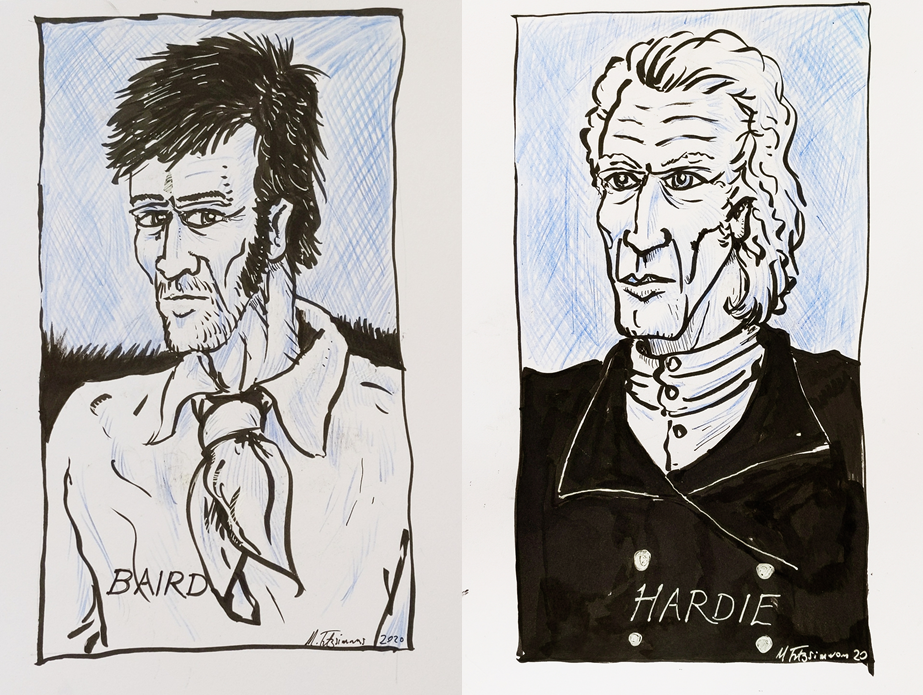

Interview between Baird and his relatives – His parting gift to his aging father – Hardie’s last letters – Preparations for the execution – How the night was passed in the condemned cell – Hardie’s remarkable coolness and self-possession – The fatal day arrives

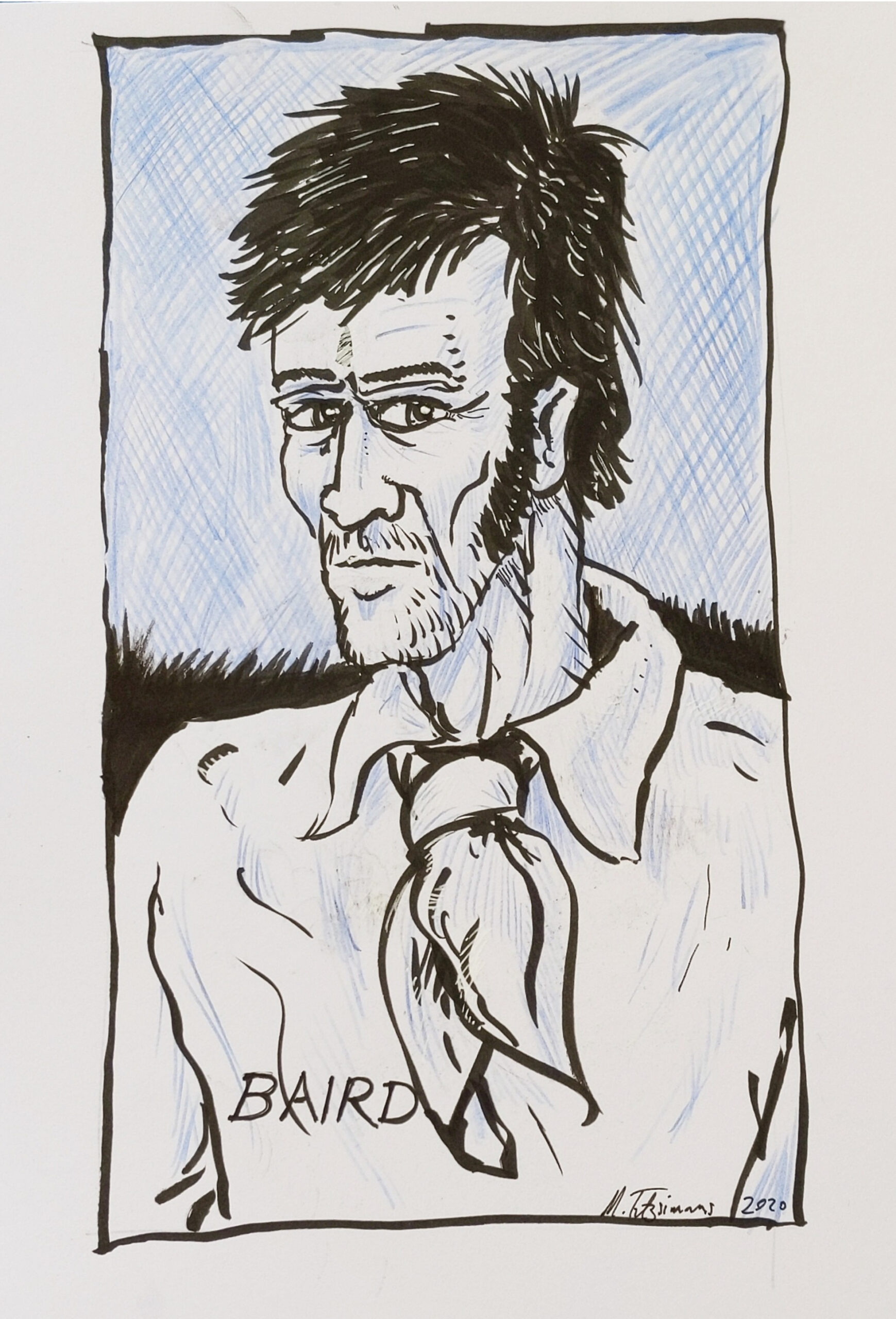

On Wednesday, 6th September, 1820, John Baird had a farewell interview with his relatives – his father (a man of eighty years), three sisters, two brothers, and two brothers-in-law. To them he detailed at length his feelings and his hopes, and called upon them to give thanks to God on his behalf, and instead of returning to mourn for his death in their own houses, to assemble their friends around them and declare what God the Lord had done for his soul. Upon those of his relatives who had children he pressed the necessity of good example to their offspring, requesting them all to live so as to be ready to die, as they knew neither the day nor the hour the Son of Man cometh. While everyone besides was dissolved in tears, he himself was firm and unruffled, and expressed himself in the softest and most soothing tone and manner. One idea alone for the moment seemed to conquer him. His aged father, whom he had not seen till now, since the day he was taken prisoner, was seated near him; he took out his snuff-box, which was a handsome horn mounted with silver, and put it into his father’s trembling hands saying – “Let me offer you this – you will perhaps look at it when you cannot look at me.” He parted with them with the greatest composure in the mutual hope of meeting in a happier state.

On Thursday, the 7th September, the day preceding his execution, Hardie wrote several letters, three of which have been preserved, the most interesting being one to Margaret McKeich, the young woman to whom he was engaged to be married. We give this touching letter in full:-

Stirling Castle, September 7, 1820

MY DEAR AND LOVING MARGARET,

Before this arrives at your hand, I will be made immortal, and will be, I trust, singing praises to God and the Lamb, amongst the spirits of just men made perfect, through the atoning blood of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, whose all-sufficient merits are more infinitely unbounded than even all the sins of the sinful world – and he is willing and able to save so the uttermost all those that are enabled to come to him by faith in his blood. What consolation does this render to me, who, while writing this, am within a few short hours of launching into an eternity where I am not afraid to enter, although a poor unworthy miserable sinner, and not worthy of the least of his notice. Yet I trust he will put on his unspotted robe of righteousness, and present my poor and unworthy soul to his Father redeemed with his most precious blood. Think, my dear Margaret, of the goodness of Almighty God to me in the last and closing period of my life. Oh, think on it, and draw consolation from the sources from whence I obtained it, and from whence consolation and real fortitude can alone be obtained. Could you have thought that I was sufficient to withstand such a shock which at once burst upon me like an earthquake, and buried all my vain earthly hopes beneath its ruins, and at once left me a poor shipwrecked mariner on this bleak shore, and separated from thee, in whom all my hopes were centred? But, alas, how vain are all the earthly hopes of us weak-sighted mortals? How soon are they all buried in oblivion? My dear Margaret, put yourself to no concern about me. O may the good and gracious God, who has supported me so peculiarly, support you also in every gracious dispensation of his providence that he is pleased to visit you with. O that he may send his ministering angels and soothe you with the balm of comfort. O may they approach the beauteous mourner and tell you that your lover lives – triumphs – lives – though condemned, lives to a nobler life. My dear Margaret, I hope you will not take it as a dishonour, that your unfortunate lover died for his distressed, wronged, suffering and insulted country: no, my dear Margaret, I know you are possessed of nobler ideas than that, and well do I know that no person of feeling or humanity will insult you with it. I have every reason to believe it will be the contrary. I shall die firm to the cause in which I embarked, and although we were outwitted and betrayed, yet I protest as a dying man, it was done with a good intention on my part. But well did you know my sentiments on that subject long before I was taken prisoner. No person could have induced me to take up arms to rob and plunder; no, my dear Margaret, I took them for the restoration of those rights for which our forefathers bled, and which we have allowed shamefully to be wrenched from us; but I trust the innocent blood which will be shed tomorrow, in place of being a terror, will awake my countrymen – my poor, suffering countrymen, from the lethargy which has so overclouded them. But, my dear Margaret, this is not a very pleasing subject to you, so I will leave it and direct your attention to matters of more importance – to the one thing needful. Recollect, my dear Margaret that we are, one and all of us, lost and miserable sinners, and that you have, as well as me, to stand before a great and just God, who is infinite and pure, and who cannot look upon sin but with the utmost abhorrence, and that it is only through the blood of a crucified Saviour that we can expect mercy at his awful tribunal. My dear Margaret, I will be under the necessity of laying down my pen, as this will have to go out immediately,

“O may God’s grace your life direct,

From evil guard your way;

And in temptation’s fatal paths,

Permit you not to stray.”

You will give my dying love to your father and mother, James and Agnes, Mrs Connell, and Jean Buchanan, and I exhort you all to a close walk with God, through our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ; and when you have fulfilled a course of life agreeable to his word, that we may be united together in the mansions of peace where there is no sorrow. Farewell – a long farewell to you and all worldly cares, for I have done with them. I hope you will call frequently on my distressed and afflicted mother. At the expense of some tears I destroyed your letters. Again farewell, my dear Margaret, may God attend you still, and all your soul with consolation fill, is the sincere prayer of your most affectionate and constant lover while on earth,

ANDREW HARDIE

Hardie also wrote a letter full of good advice to a young friend in Stirling, Isabella Condy. This letter was addressed as follows:- “From Andrew Hardie to Isabella Condy, as a token of gratitude for her kind attention to him while a prisoner in Stirling Castle, who fell a martyr to the cause of truth and justice on the 8th September, 1820. Stirling Castle, Thursday night at 10 o’clock, 7th of September, 1820. To Isabella Condy, Stirling.”

The last letter was written an hour later. It is not included among the letters printed by Peter Mackenzie, and we are indebted to a Stirling shoemaker for a copy of it.

MY DEAR YOUNG FRIEND,-

According to promise, I write you a few lines, and as the hand that now writes will in a short time be smouldering in nature’s dust, I hope you will take into serious consideration the uncertainty of our time in sojourning in this world, and remember that this is not our resting-place, and that if you try to make a resting-place of it you will be sorely disappointed. But I hope better things of you. I trust you will seek that rest in heaven, where it can be obtained only. I earnestly entreat you as a dying man, and as one who has experienced that goodness of God in affliction, to keep a close walk with God through our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, who is willing and able to receive and support all those who come unto him through faith in his blood. Remember what he suffered for us, poor miserable lost sinners, and…what we ought to render in return for his great and unbounded love to uswards. And yet he requireth nothing but our hearts. I leave you this, my dear young friend, for your serious consideration. I should have written you much more, but my time of dissolution is fast approaching. I shall now bid you farewell; a long farewell to this vain world and all its boasted pleasures, for I have done with them.

“O may God’s grace your life direct,

From evil guard your way;

And in temptation’s fatal path,

Permit you not to stray.”

From, my dear young friend, your dying brother in Christ,

ANDREW HARDIE.

Stirling Castle, Thursday night, 11 o’clock.

To Alex. Gibb, shoemaker, Alloa.

———

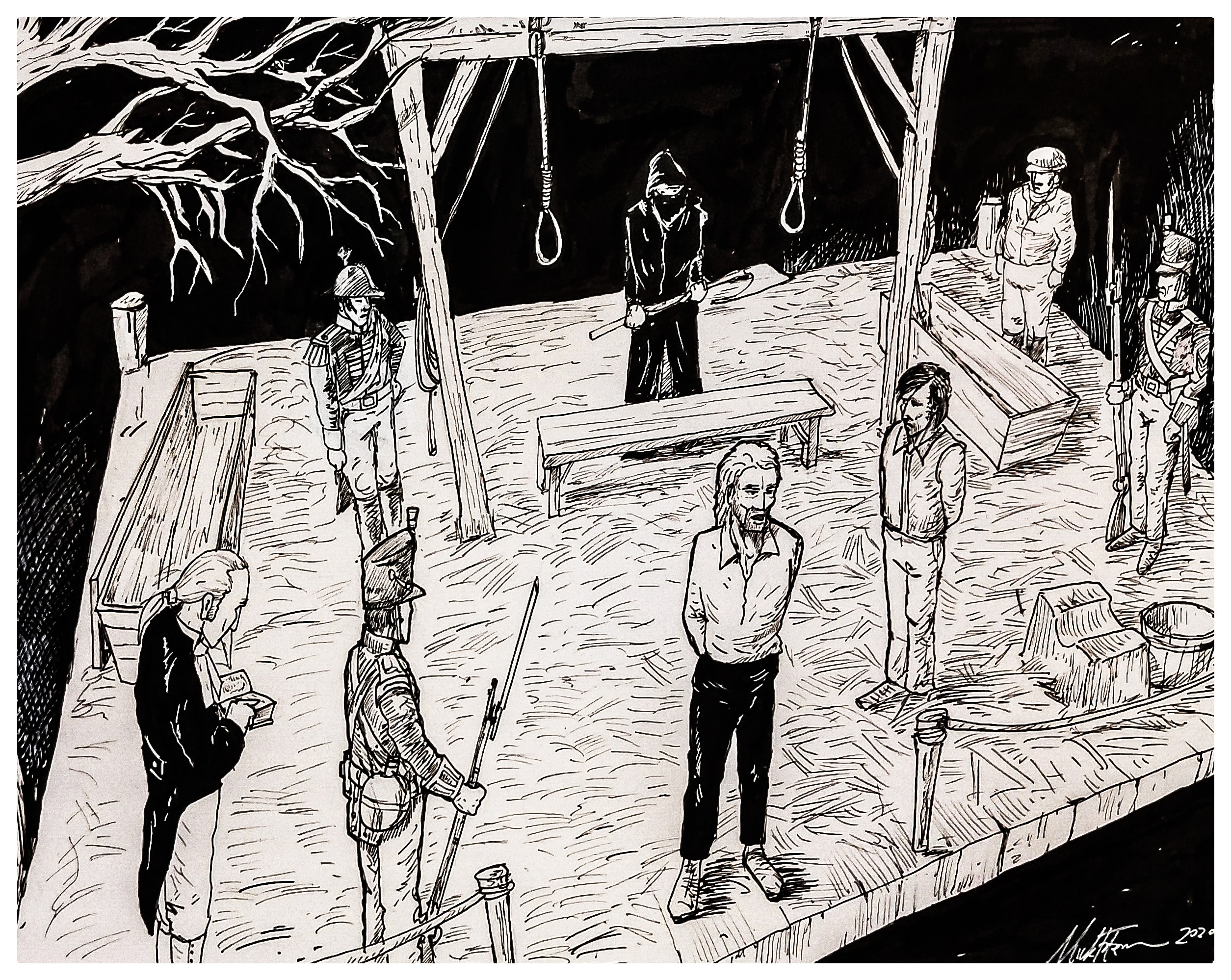

While this letter was being written, workmen were proceeding with the erection of the scaffold in Broad Street, which was begun at half-past ten o’clock and finished next morning. Two coffins containing sawdust, one bearing the inscription “Andrew Hardie, aged 27,” the other, “John Baird, aged 37,” were placed upon the scaffold, a board, covering about a third of the coffin, was placed to support the breast of the body; a square tub, in which there was a considerable quantity of sawdust, was placed at the head of each coffin; and to the side of the tub, nearest the coffin, was fixed a block. A troop of the 7th Dragoon Guards arrived about eleven o’clock and proceeded by the back streets to the Castle.

From the period of their condemnation (says an eye-witness who attended to them) they had been daily visited by the Rev. Mr Bruce, and occasionally by the Revs. Drs Wright, Small and Heugh. Such was the rapid advancement they had made in the Christian life, that some of these rev. Gentlemen declared on the night preceding their execution, “that they had come rather to learn than to communicate instruction – rather to witness the triumph of divine grace and to see the salvation of the Lord, than to perform any service.” It was the wish of Hardie and Baird, who at this time were in the same cell, to spend the whole of their last night on earth in private prayer to God; but some of their nearest relatives had expressed a wish to be permitted to pass this night along with them. This request, General Graham, the governor of Stirling Castle, who invariably treated the whole of the prisoners with the utmost kindness, readily granted, and also ordered a sergeant of the garrison, a pious man who belonged to the Methodists connection, to attend them with refreshments &c. The night was spent alternately in reading the Scriptures, in prayer and in conversation; and so cool and collected, nay so happy and cheerful were they, especially while engaged in prayer and praise, that they appeared more like men enjoying a triumph than enduring a trial, more like saints made perfect in bliss than men about to undergo an ignominious death. During the intervals of conversation, Hardies inquired of his cousins into every particular that could be interesting to them, to his other friends, or to himself. He wished to know all the arrangements they had made regarding him, whether they had got a strong coffin made, how his corpse was to be conveyed to Glasgow, and he even examined his winding sheet which they happened to have with them! About four o’clock in the morning, Hardie and Baird lay down in bed together and slept for two hours, apparently as soundly as ever they did in their lives. We are giving the narrative of one of the rev. Gentlemen who attended the unfortunate men, but the Stirling Journal, which commenced in July 1820, and gave a long account of the execution, says they did not enjoy anything like the softness of refreshing sleep.

Agreeable to their own request, they were wakened at six, when they washed and dressed and felt greatly refreshed. The Journal says they complained in the morning that their breasts were a little pained with singing the psalms and hymns in the course of the night; but both admitted that their minds were, more at ease and their confidence more enlarged than on the day before. It had been their wish to wear a white pair of trousers along with their black coat and vest, but their friends recommended them to appear all in black, and this course was adopted. After they had dressed, they sang the first four verses of the 51st paraphrase, evidently with the spirit and understanding also; Baird then read from the 20th verse of the 15th chapter of 1st Corinthians to the end. Then he engaged in an agony of prayer to God, the burden of which was that he would strengthen their faith and stand by them at the trying hour. This was perhaps (says the clerical narrator) one of the most powerful, comprehensive and affecting prayers that ever were offered up. The Rev. Mr Watson, from Edinburgh, and the Rev. Mr Bruce, and Drs. Wright and Small entered the prison during these exercises; but in the prayer they were all in tears; indeed, Hardie and Baird were the only individuals present that were not deeply affected. They appeared already to have obtained the strength of faith, and that divine aid which they were so anxious to secure. About a quarter past twelve noon, all but Mr Bruce finally left them. They seemed extremely grateful for the attention which had been shown them by that clergyman, and begged of their relatives never to forget it. On this occasion, also, they both requested of Mr Bruce to return their thanks to Mr Heugh for the interest he had taken in their situation. Hardie remarked that he had thought of doing so in writing, but the multitude of subjects pressing upon his mind had prevented.

To be continued…