This is the second section of Chapter VI of the serialisation, the wording reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, on Tuesday 19th March 1889.

We have before us several accounts of the “Battle of Bonnymuir” – that short, sharp struggle between a handful of half-fed weavers and a troop of well-equipped cavalry – and we select for republication, the most graphic and as far as we are able to judge, the most truthful of these. It was written by Andrew Hardie in his cell in Stirling Castle, a few days before his execution, and has therefore a peculiarly pathetic interest.

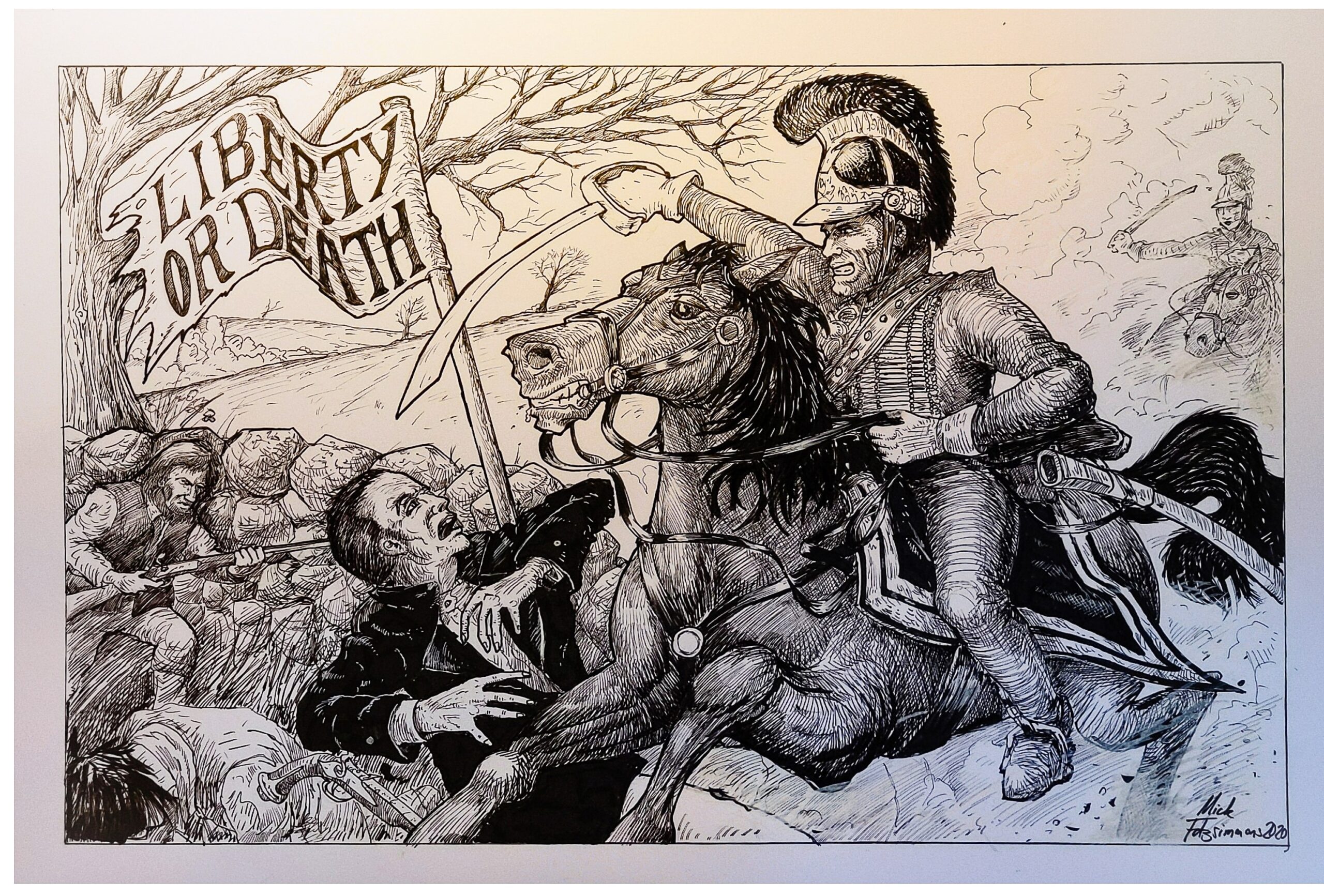

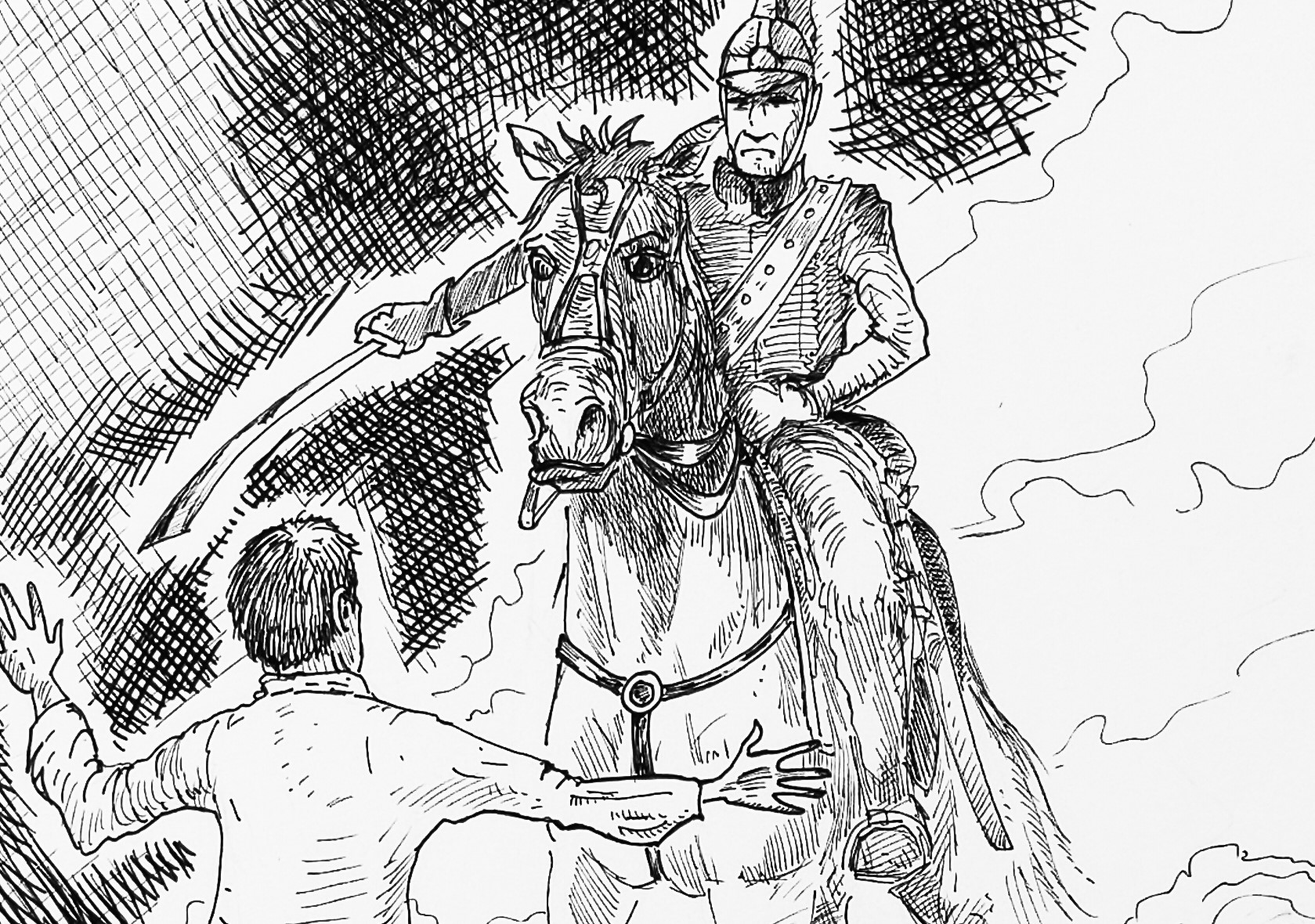

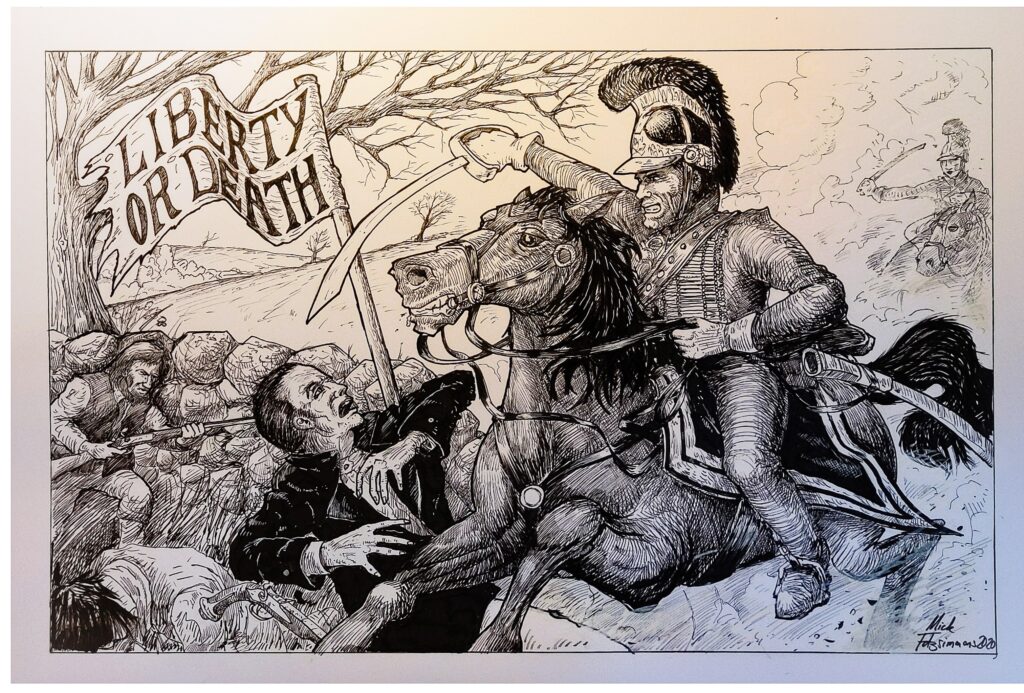

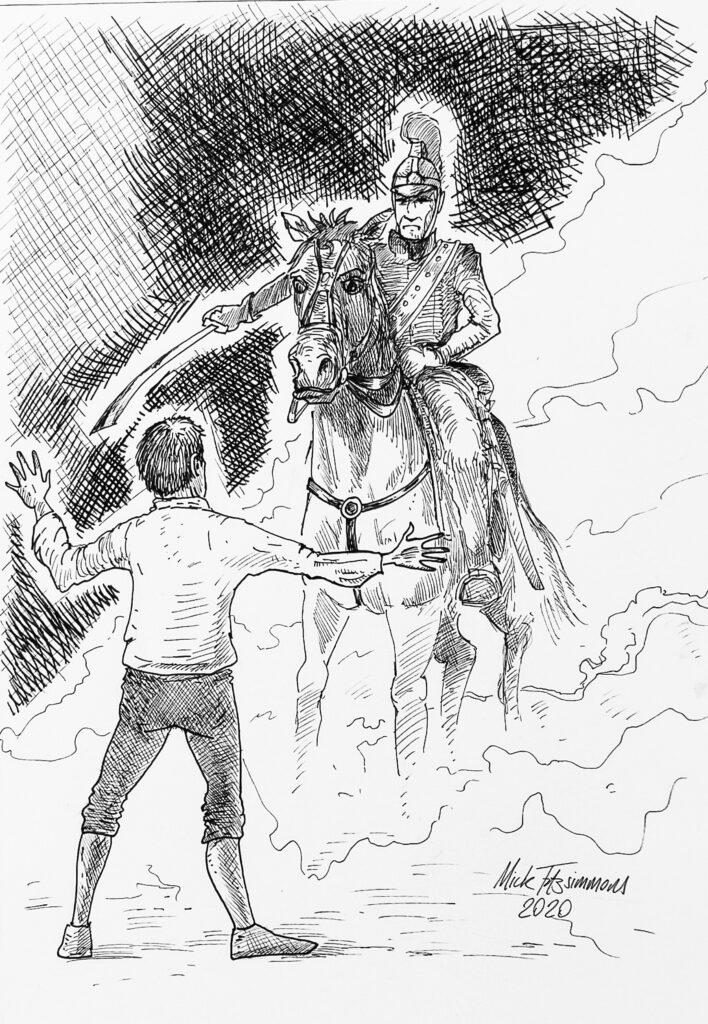

“We went up about a mile into the moor, and sat down on the top of a hill, and rested, I think about an hour, when the cavalry made their appearance. Upon this we started to our feet, and at once resolved to meet them. I proposed forming into square where we were but Mr Baird said it would be much better to go undercover of a dyke which was not far distant. We then ran down the hill cheering and took up our position. There was a slap in the dyke which we filled with pikemen. The cavalry took a circular course through the moor and came under cover of a wood at our right flank. As soon as they made their appearance past the end of the wood, firing commenced immediately. I cannot say who commenced firing first. I think the cavalry had fired a shot or two before they came to the wood with the intention, probably to frighten us, for they told us afterwards they did not expect us to face them. However, this is a matter of no importance. They came up nigh to the dyke, the Hussars in front led by their officer, who called out to us to ay down our arms, but this was not agreed to. After firing some shots at us they made an attack at the slap, and got through, but were repulsed and driven back; they, in general, stood a little distance from the dyke, so that our pikes were rendered unserviceable. One of the Hussars came up close to the dyke, a little to the right of where I stood, and one of our party made a stab at him.

The Hussar fired at us in return, and he fell forward on his face. They made a second attack at the slap, and got through but were kept at bay in the inside, and the officer again called out for us to surrender, and he would do us no harm, which most of our men took for granted, and threw down their arms and ran. It will be here necessary to observe that some of our men never came into action at all but made their way into a wood at some distance.

But those who tried to make their escape after our surrender (viz., after the officer had called out a second time, and by this time was in the inside or our side of the dyke) were instantly pursued, but were not all taken, and some of them wounded in a most shocking manner; and it was truly unbecoming the character of a British soldier to wound or try to kill any man whom he had it in his power to take prisoner, and when they had no arms to make any defence. One of the yeomanry (the Kilsyth Yeomanry Cavalry accompanied the 10th Hussars), was so inhuman, after he had sabred one of the men, sufficient as he thought to deprive him of life as to try and trample him under his horse’s feet; but there my friends the horse had more humanity than his master, and would not do as he wished him but jumped over him, in place of trampling upon his wounded and mangled body; and after he returned from doing so, he called out (speaking very broad) ‘that he’d left him lying with his head cloven like a pot.’ There were several other wounded but I will not say any more about them, as I suppose you have heard all the particulars long before this.

“Mr Baird defended himself in a most gallant manner; after discharging his piece he presented it at the officer empty, and told him he would do for him if he did not stand off. The officer presented his pistol at him, but it flashed and did not go off. Mr Baird then took the but end of his piece and struck a private on the left thigh, whereupon the sergeant of the Hussars fired at him. Mr Baird then threw his musket from him and seized a pike, and while the sergeant was in the act of drawing his sword, wounded him in the right arm and side. Before this the officer was wounded in the right hand, and his horse also was wounded, yet, notwithstanding, he would not allow one of his men to do us any harm, and actually kept off with his own sword, some of the strokes that were aimed against us. One of the Hussars recognised one of our party who (he said) wounded his officer, and would have instantly sabred him had not the officer speedily interfered and told him there was too much done already. Although my enemy, I do him nothing but justice by saying that he is a brave and generous man. He came up in front of his men, and I am truly happy (but surprised) that he was not killed, as I know there were several shots fixed at him. After the wounded men, and those who tried to make their escape were all brought together, we were taken off the moor. Mr Baird and I had assisted one of the wounded men until we got to a cart, and as they were put in it; one of them was dreadfully wounded in the head, I think in four places and shot in the arm. Another old man with a frightful looking wound in his face, so much so that his jawbone was seen perfectly distinct; and a third, had a sabre wound in his head, and had been left on the field for dead; but I was truly happy to hear afterwards that he was not so, but that they had recovered and got safe off. The officer of the Hussars asked who was our captain and if his name was Baird, which made it evident that some person who knew him had given them information. We were all very fatigued by being up all night, and having got no victuals but what is before mentioned, viz., a penny loaf and a drink of porter, we made application to the officer of the yeomanry to let us halt and get a drink of water, but alas! That small favour could not be granted, for it must be observed that the officer of the Hussars was at this time absent getting another horse, as his was so wounded it could carry him no further. When he came up to us he granted our request immediately.

After we arrived at Stirling we were all put into one room, and being uncommonly tired it was not long before most of us buried all our cares in a sound sleep, having previously obtained some bread and water. Mr Baird and I went to bed together but he was taken away from us shortly after and put into a dungeon, and had about four or five stones of irons put upon him. Hardie also wrote a description of the event in rhyme, the following being two of his verses: –

“Men and horses in armour bright, advancing speedily in our sight,

Up we sprang, to arms we flew, and this we then designed to do,

Close to the dyke to run with speed, and then to face the prancing steed;

To keep them back as long as we could, or in the cause to shed our blood.

With anxious eyes we looked in vain, to see this hero and his train,

To help us in the time of need against the rider and his steed.

Firing commenced on every side, swords and pikes did next succeed,

Thro’ the dyke a few advanced, but back we drove them with the lance.”

Eighteen prisoners were brought to Stirling and their arms, consisting of a musket or two, a pitch fork and a number of pikes, were carefully preserved by the armourer at the Castle for production at the trial.

To be continued, Tuesday 27th October