Introduction

In the true spirit of a radical Glasgow tradition, the organisation Living Rent are currently involved in a campaign of direct action to stop the 300 planned evictions of asylum seekers, by Serco Group PLC. This important campaign has attracted widespread support from a range of activists across the city.

Community-minded legal organisations such as Latta Law, Govan Law Centre, Shelter and Legal Services Agency (LSA) have all pledged to continue to lodge legal challenges to each and every eviction notice issued by Serco Group PLC, and have been successful in obtaining interim interdicts in all the cases brought to their attention (around 80 individual cases). Unfortunately, though, it seems that at least three cases have slipped through their legal net where campaigning groups do not appear to have been informed of the impending eviction and/or the tenant assuming that little could be done to prevent it.

The Political Context

Serco Group PLC, a FTSE top 250 company, won the Home Office contract in 2012 to house asylum seekers while their claims were being assessed. This multinational, which manages over 500 contracts worldwide, and operates in the UK & Europe, North America, Asia Pacific and the Middle East lost the recent contract to the Mears Group who will commence responsibilities for asylum seeker accommodation in September 2019. In the meantime, Serco have stated that they will be evicting 300 of their Glasgow tenants who they claim have ‘failed’ in their attempts to be granted asylum in the UK. Originally set for the summer of 2018, these evictions have been postponed due to a range of legal challenges and political pressures from a broad section of the community. Serco have stated that they will commence with around 30 lock-changes a week.

The Legislative Context

These evictions are taking place within a much bigger legislative context. The Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016, the central pillars of the then Home Secretary, Theresa May’s ‘hostile environment for immigrants’, actually set out to criminalise both immigrants AND the general public, if they fail to comply with its prescriptions. This is relevant to Glasgow’s asylum seekers because the 2014 Act makes it a criminal offence to let accommodation to any person who does not have ‘the Right to Rent’. This means that anyone who has not been officially granted ‘leave to remain’ is prevented from accessing accommodation ANYWHERE in the UK. The 2016 Act has not yet been enacted by the Secretary of State for Scotland, so for the time being only applies to England and Wales. The 2014 Act criminalises landlords and entails a fine while the 2016 Act extends the punishment to 5 years imprisonment for non-compliance. It’s not just landlords who can potentially be criminalised, the Act criminalises bank workers who allow undocumented migrants to open bank accounts, as well as driving instructors who give driving lessons to people who do not have leave to remain. The implications of this are significant:

- Britain’s borders are no longer restricted to airports or sea ports, they now include every inch of public and private space in the UK. Through the process of potential criminalisation, the UK government has, in effect, turned the entire population into border guards, responsible through the threat of imprisonment or fine, for the ‘policing’ of immigration in an unbounded border that now exists everywhere.

- The Immigration Acts foster ‘racist’ practices that damage community cohesion and weaken social solidarity. Research by the University of St Andrews has shown that these Acts make people wary of dealing with anyone they think may be ‘foreign’. The evidence shows that landlords are much less likely to consider letting a property to anyone with a foreign name, or an accent or even an appearance that is not ‘obviously’ British. ‘Legal’ migrants in this country have a hard-enough time finding suitable accommodation as it is, the Immigration Acts have made it a whole lot worse.

- Punitive Acts that seek to criminalise the public for non-compliance in state-sponsored forms of racial oppression have ideological functions that not only assist the powerful in exercising its domination, but which allow the State to further encroach on the lives of its citizens. The State increasingly becomes a surveillance state, a punitive State, a paternal State. In short, the ‘Nanny State’ of the Fordist-Keynesian period that saw the birth of the NHS, social housing and full employment, as well as unprecedented levels of immigration to the UK, has steadily been replaced by the ‘Daddy State’, one that seeks to discipline and punish rather than provide assistance and care.

The Rightward Tilting of the Bureaucratic Field

In order to adequately understand this process it is useful to understand the rightward tilting of the bureaucratic state. The rightward tilting of the bureaucratic field is a process that has enormous relevance to the current situation regarding immigration policy in the UK. This conceptualisation also helps explain a variety of different public and social policy interventions, as well as accounting for recent developments in the practices in ‘welfare’ provision and the delivery of public services. The bureaucratic field is a key component of the wider field of power, which constitutes the State. In this paradigm, the state is not a unitary monolith of governance, which, headed by a ‘ruling class’, serves the interests of a specific group. It is, rather, an arena within which various groups, entangled in a network of co-operative competition, struggle for the monopoly over the legitimate right to define issues, such as social problems, the solutions to which arise from the process of selecting which problems warrant recognition and which are to be ignored.

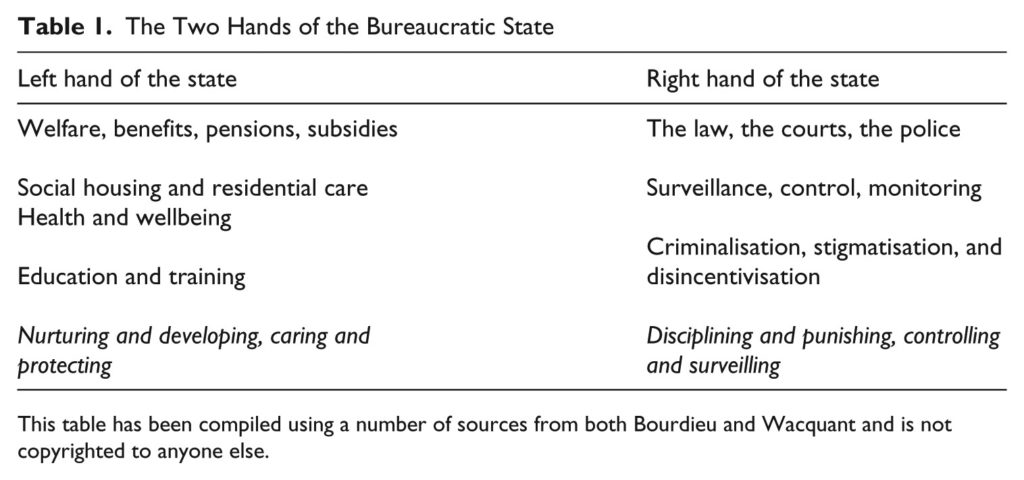

The bureaucratic field is structured around the notion that the ‘left hand’ of the state is perceived as the nurturing side, which is responsible for the welfare of its citizens. The ‘right hand’ of the state is made up of the disciplining institutions, which, by contrast, punishes, polices, controls, and incarcerates. Both the left hand and the right hand exist in antagonistic cooperation (since they occupy different positions within the bureaucratic field, and therefore have differently corresponding political outlooks as well as being driven by differently corresponding internal logics). The rightward tilting of the state is the increasing intervention by the disciplining institutions in issues and problems that would have previously received the almost exclusive attention of the left hand of the state, such as welfare and support, social housing, benefits, health, and education. The dual effects of both privatisation and increasing levels of ‘regulation’ and ‘inspection’ have had a long-standing effect on public services in the UK, a fact which has resulted in services being run according to business models while at the same time being much more proactive in promoting policies with surveillance and the modification of behaviour as a principle objective.

This shift from the left to the right hand of the state has resulted in the double regulation of those who are at the periphery of the employment sphere, that is, those who are situated in the precarious regions of the lower strata of social space.

The civil tensions and unease created by unemployment and austerity, unfurling through disciplinary supervision over the precarious fractions of the post-industrial proletariat, creates a behaviour changing welfare system, a work-enforcing benefit system, a rent enforcing social housing system, as well as a debt enforcing credit system, all of which are configured to modify behaviours and to foster the surveillance of ‘risky’ groups. In the context of this study on immigration controls, particularly with regard to housing, this ‘rightward’ tilting of the State promotes a regime, which in cases such as the implementation of the Right to Rent prioritises ‘status’ crimes over crimes of conduct. Nowhere is this shift more visible than in the binary forms of categorisation that emerge from the wide range of oppositions, which govern the practices of landlords. These sets of inescapably cognitive and evaluative presuppositions paradoxically unite those whom they divide, since agents have to share a common acceptance of them in order to fight over them or through them, and so to produce position takings which are immediately recognised as pertinent and meaningful by the very agents whom they oppose and who are opposed to them.

It is within this governing tension, between the left and right hands of the state, that the binary oppositions, such as those who are either ‘deserving or undeserving’ of assistance, who are ‘citizens or non-citizens’, ‘genuine or bogus’ asylum seekers, ‘real or fake’ victims of trafficking, or ‘legal or illegal’ subjects, are legitimised and in turn prioritised by institutions of the state. What the data from this research show is that the binary oppositions and the governing tensions, from which they arise, create the forms of discrimination that constitute the dichotomous positions between the government and the social housing sector in Scotland.

By shifting from a focus on the criminalisation of conduct to the criminalisation of status within immigrant groups, and by enforcing this through a punitive threat of 5 years in prison for non-compliance, the government succeeds in the modification of behaviour in both immigrant groups and in landlords. As the interview data has shown, this is not something that housing professionals simply accepted without question. The next section will offer a discussion of the sociological principles which help explain some of the governing tensions within and beyond the state.

What is to be Done?

What are the implications then, for Glasgow’s asylum seekers, who face illegal lock changes at the hands of Serco and the Home Office? Firstly, Living Rent are right in calling these actions inhumane. The campaigners are also right to demand that Glasgow City Council (GCC) defy the Home Office and offer those affected, emergency accommodation. However, these are very short-term solutions.

Of one thing we can be absolutely certain; Serco Group PLC and Mears Group, care much more about shareholder value than the lives of those they are paid to accommodate. Secondly, the root of the problem is neither the outsourcing multinationals nor Glasgow City Council but rather, it is the UK government at Westminster. Therefore, an effective solution requires the protection of the vulnerable in Scotland from the authoritarian, punitive and populist policies of a racist and xenophobic Westminster, while at the same time safeguarding Scotland’s future from the destructive and oppressive Westminster political regime.

Serco, acting under the provisions of the Immigration Act 2014, intend to carry out what in Scotland we call ‘summary evictions’, without following due process. The law in Scotland precludes ‘summary evictions’ and in fact deems them to be a criminal offence under Part III, Section 22 of the Rent (Scotland) Act 1984. A landlord who evicts without a decree from the Sheriff Court can, as prescribed by this Act, be given up to two years in prison. The problem is trying to get the police to take illegal evictions seriously (an important research article for another time).

Housing legislation within Scots law, including protection from eviction, has a rather longer history than England and Wales, with the first statutory regulation of evictions prescribed as long ago as the Act of 1555. This was passed ‘to rid the country of the violence which was a usual accompaniment to the older removings … on verbal warnings only’ (Rankin 1916: 550 quoted in Stalker 2007: 4). The 40-day notice period emerged from the 1555 Act which also stated that failure of the tenant to heed such notice could result in the landlord seeking a legal remedy in the form of a decree for eviction in the Sheriff Court. Once the decree had been granted, the ‘landlord had then to apply directly to the local Sheriff for a warrant of ejection’ (Stalker 2007: 4). What seems remarkable about this early form of eviction procedure is that the two foundational aspects have survived to be very much part of eviction proceedings today. There is still a requirement to issue notices, and there is still a legal requirement to acquire a decree from the sheriff court, the granting of which requires that a sheriff officer be instructed to oversee the eviction. The law governing eviction changed only slightly between the 1555 Act and the Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1907, which provided the means by which the ‘decree for removing’ and the ‘warrant for ejection’ could be obtained as part of the same single process (Stalker 2007). Today, the procedures for eviction are similar in England and Wales, their history, however, is nowhere nearly as long.

Thus, with history on his side, Mike Daily of the Govan Law Centre represented two Kurdish women from Iraq and Iran against the Home Office and Serco in August 2018 at the Outer House of the Court of Session in Edinburgh. His argument was simply that it was unlawful in Scotland to carry out a summary eviction. In a 29-page report Lord Tyre found in favour of the Home Office saying “I am satisfied that neither of the pursuers has made out a relevant case for any of the orders sought.” The Govan Law centre are set to appeal the case.

The first problem is that we have here a case whereby a series of illegal evictions carried out in Scotland at the behest of Westminster’s legislator is severely undermining the fundamental protections of vulnerable people, enshrined in Scots Law. The second issue is that housing is a devolved matter for the Scottish Parliament, while immigration is reserved to the competence of Westminster. Being markedly different countries in a number of important respects, this causes Scotland a range of problems. For one, it is damaging the economy of Scotland, a country that relies on immigrant and seasonal labour for agriculture and tourism. Also, as we have seen, it creates unresolvable tensions, when the two laws, and political cultures, conflict.

This brings us onto the second problem, which has the most obvious solution. Since the laws that underpin the problems faced by Glasgow’s asylum seekers are generated by Westminster and implemented by the Home Office in London, then we need to negate (not reform) the power that Westminster and the Home Office have over us here in Scotland. Here we have a situation where the protections provided by ancient Scottish laws are being trashed by a Westminster elite whose politics are, as has been the case for some years now, completely antithetical to those of the Scottish people. There is only one realistic way to resolve this. Every single aspect of the campaign to stop the inhumane lock changes and the forced removal and destitution of asylum seekers must be underpinned by an overarching demand for Scottish independence. There exists no long-term solution without it.