This is the first section of Chapter VI of the serialisation, the wording reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, on Tuesday 19th March 1889.

THE “RADICAL ARMY” HESITATES – RESOLUTION TO PROCEED – HOW KING, THE SPY, LAID A TRAP FOR HIS VICTIMS – A POOR BREAKFAST – HOW THE BILL WAS PAID – A ‘BRAVE’ YEOMAN – THE RADICALS AND THE HUSSAR – BETRAYAL OF THE RADICALS BY THE SPY – THE ‘ARMY’ IN THE TRAP – HARDIES ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE OF BONNYMUIR – A PLUCKY STAND – A GENEROUS ENEMY – THE CAPTURED PRISONERS AT STIRLING CASTLE.

The Radical army of thirty-five individuals, which arrived at Condorret on the morning of Wednesday, 5th April, 1820, seriously considered whether it would not be desirable to stay there until the expected reinforcement from Anderston, or disperse as quietly as possible. The latter course would not have suited the purpose of King, the spy, who knew the military were on the road, and that if the party were to keep together for an hour or two longer, they would be taken in arms against the Government. He therefore strenuously opposed the proposition, and represented that if the party moved forward they would be joined by numbers of friends at Camelon and Falkirk, and he offered to go on in advance and get the recruits ready before the main body of the army came up.

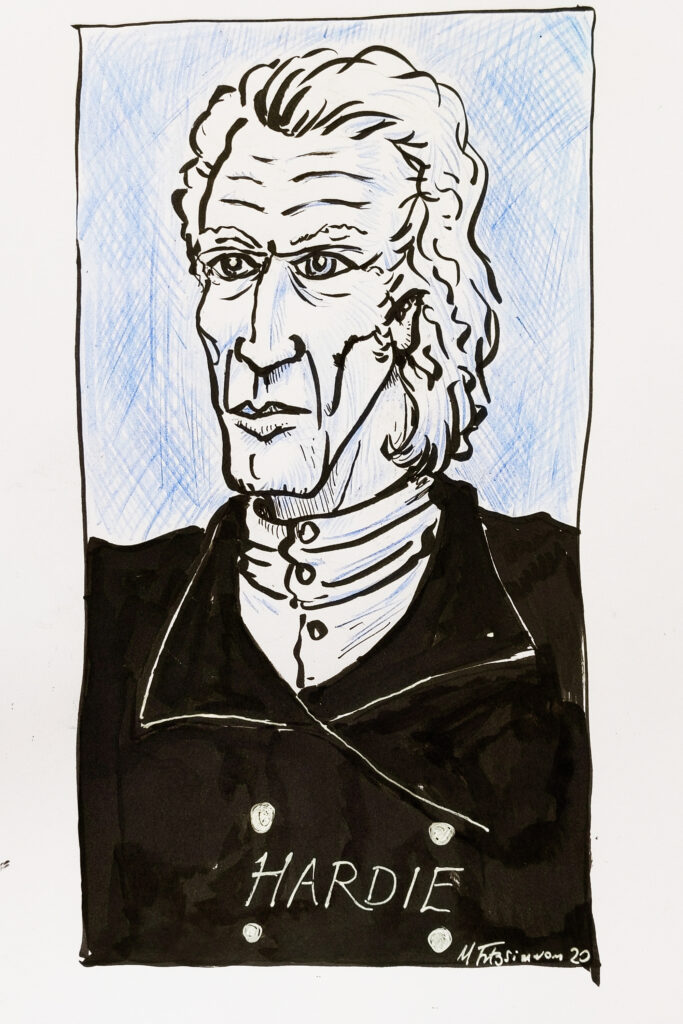

It is almost inconceivable how Baird and Hardie allowed themselves to be duped by such a miserable subterfuge, but they looked upon King as being armed with powers from the secret committee, and firmly believed he could command adherents to the cause wherever he appeared. Before leaving the party at Condorret, King took the precaution to see that John Baird was elected the leader of the expedition, with Andrew Hardie second in command. The first halt was at Castlecary Bridge, where the party went into a public house and had breakfast, consisting of porter and bread. The reckoning came to 8s, and Baird tendered 7s 6d, for which he asked a receipt, which was given by the landlord in the following terms, dictated by Baird: – “the party called, and paid for porter and bread, 7s and 6d by cash; (signed) Archd. Buchanan.”

Peter Mackenzie said the Radicals asked the innkeeper if he would take a bill from them for the eight shillings at six months’ date, on the Provisional Government at Glasgow, but this is an exaggeration. The innkeeper was asked at the trial if Baird, whom he described as a little man, had proposed he should take something else instead of the money, or said anything about a note, but the answer to both questions was in the negative. The landlord also said that Baird paid the money out of his own pocket. It was the Lord Advocate who told the story about the bill, and made fun of the party not having enough money among them to pay the reckoning and it is somewhat surprising to find Mackenzie accepting the anecdote on testimony which he takes every opportunity of impugning. It is possible enough, however, that Baird insisted on getting a receipt in the belief that he would ultimately be repaid by the Provisional Government. Acting on King’s advice, the party now divided, one branch , under Baird, taking the route by the banks of the Glasgow and Edinburgh Union Canal, and the other under Hardie, keeping the turnpike road lest they should miss any of the friends coming to join them.

The party on the highway soon met a gentleman on horseback on his way to Glasgow. They stopped him, and on learning his destination, they beseeched him not to prosecute his journey, because there was sad work going on in Glasgow. This was said of course, because they believed King’s assurance that a Revolution was taking place in Glasgow, and they wished to give the traveller a friendly warning. He hesitated wether he should take their advice or go on, but resolved to proceed, and a mile further on he met a mounted trooper of the Kilsyth cavalry of whom he anxiously inquired the state of Glasgow, stating at the time that he had encountered a party of armed men who gave him most alarming intelligence. This ‘brave’ member of the yeomanry corps, Nichol Baird by name, was so taken aback by the news that he could not utter a word and he turned and rode back to Kilsyth without going up to the Radicals, though he sore at Hardie’s trial that he had been attacked by them on the road and successfully resisted them! The traveller, seeing he could get no satisfaction, rode back in the direction of Hardie and his party, and as he passed he told them that he now thought it best to follow their advice, and that he was going back to Stirling, from whence he had that morning started. The gentleman was enquired after in the expectation that he would give evidence in Hardie’s favour, but he could not be found, and it was not until twelve years later that he was discovered by Peter Mackenzie, and gave his story, which established the cowardice of Nichol Baird, and also the perjury he committed at the trial. He was an English traveller and had gone to the safer side of the Border as soon as he was able.

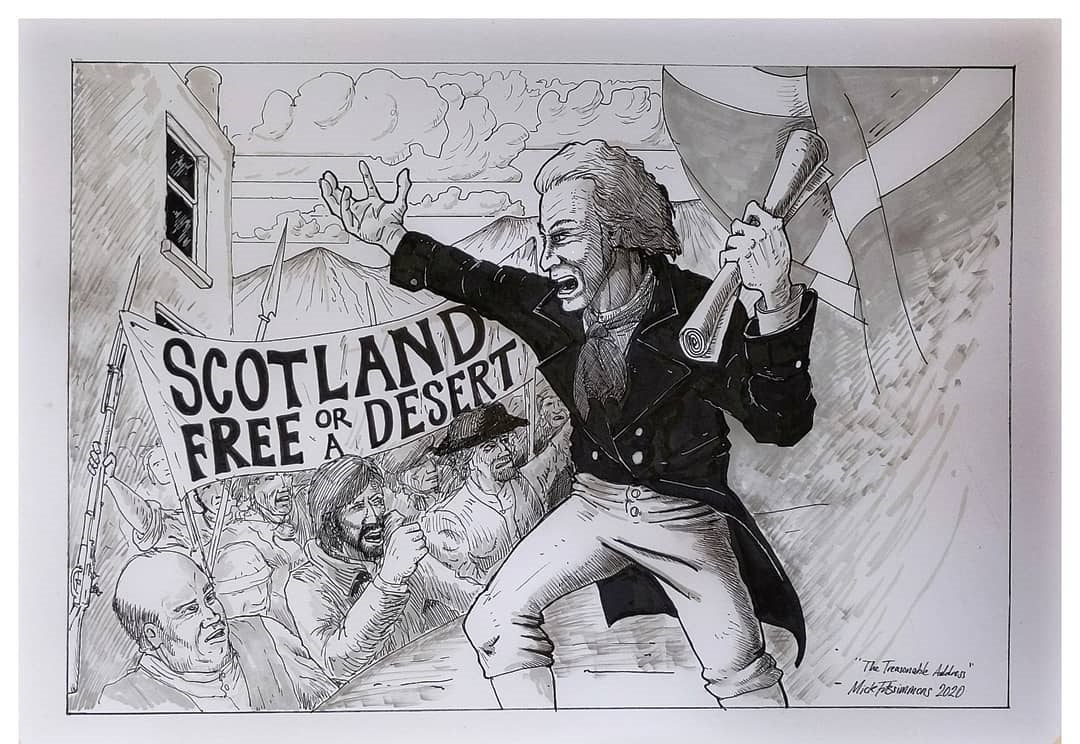

Hardie’s party, on the high road, met another person whose presence there should have been sufficient to prove to them that they were being led into danger. This was a soldier belonging to the 10th Hussars. Why did the Radicals not see at once that Turner, when he assured them they would not meet with any of the military on their way to Carron and back, was telling a falsehood and that their lives were imperilled by the treachery of their leaders? No doubt they imagined that, as Turner had said, the military were in favour of the Radical cause and were prepared to join them. A fatal error indeed! In this belief they were ready to embrace the first soldier they met. They accosted the Hussar, Cooke by name, and asked him where he was going. He answered that he was going to Kilsyth, and on his asking them in return what they were wanting, they replied that they were seeking their rights, but would do him no harm; whereupon Cooke assured them that he was a friend of their cause, and then one of the party (not Hardie) pulled out a roll of the Treasonable Address, and gave a copy to the Hussar, who pursued his way to Kilsyth, where the first thing he did was inform his superior officer of what had occurred on the road.

Meanwhile, where was King? Not at Camelon or Falkirk, where he said he was going but skulking about the banks of the canal. He seems to have joined Hardie’s party about a mile and half past Bonnybridge, but how could he have been received without suspicion of treachery it is impossible to understand. At his insistence a signal was given to Baird’s party to join Hardie’s, and when this was done, King told them to up to the adjoining moor and wait there until he came up with his promised reinforcement from Camelon. With the exception of one or two, the whole of the party obeyed this direction and marched to the bleak and hungry looking waste, where they unanimously resolved not to proceed a single step towards Carron or any other place, unless the promised reinforcement actually arrived. It was also arranged among the Glasgow contingent that they would remain on the moor and return separately to Glasgow in the evening to ascertain distinctly what was doing there. If they had been left to carry out this programme, there would have been no “Battle of Bonnymuir” to record and Baird and Hardie would probably have lived to laugh over their foolish exploit. But a battle there must be, if it is only to prove that the Government are not befooling the people.

Lieutenant Hodgson, when he gets the treasonable address from Cooke, the hussar at Kilsyth, does not read it – he has seen one the day before in Stirling – but gives orders for a march in the direction of Falkirk and Carron. Now, the military might reach either of these places without going near the moor where the Radicals are waiting for the reinforcements that never come, but at or near Bonnybridge Lieutenant Hodgson gets intelligence which way the men who stopped Cooke have gone, and is directed to the part of the moor where they are to be found. Who gives the officer this information? Hodgson does not tell when he comes before the court – he is not asked the question – but we know now. It was the villainous spy, King, who sent the poor weavers to Bonnymuir, and then sent the military to shoot them. This rascal, who changed his name frequently to suit his purpose, afterwards disappeared; his execrable task was accomplished and he was needed no more.

To be continued on Thursday 22nd October