This is the second and final section of Chapter III of the serialisation, the wording reproduced exactly as it appeared in the Stirling Sentinel, on Tuesday 26th February 1889.

This worthy tells us how the officials of the Government felt this defeat. “When I called”, he says “upon the Crown lawyers next day to learn the particulars of the trial, they appeared like chagrin and mortification personified. Mr Drummond attributed their failure to a want of management in not, in the first instance, making sure of evidence to produce a conviction….As I had frequent opportunities of unreservedly hearing the sentiments of the Crown lawyers during the progress of the trial, I will state the impression produced on my mind as to the original intention of the measures framed.

Had they, in the first instance, succeeded in establishing the administration of the oath, on which they entertained no doubt, two or three would have been sentenced to capital punishment and a number more to transportation; and had the circumstances which I have related not intervened, I have no hesitation in saying that these sentences would have been carried into execution”. We may believe this statement or not as we choose, but there can be no doubt upon this point, that if any of the prisoners had been executed, Richmond the spy would have been a murderer, as he afterwards became when, by his means, Baird and Hardie were sent to the scaffold.

A temporary calm followed the fiasco of 1817, but in the following year the demand for Reform was again loudly made, and public meetings and inflammatory harangues became common throughout the country. An organisation was formed in London for the purpose of coping with the Government, and the agitators in some places began a series of nocturnal military trainings. The unfortunate meeting at Manchester in August 1819 – the massacre of Peterloo – roused the people to fury, and the Government, unmindful of the lessons of the past, instead of granting harmless concessions which would have satisfied all reasonable men, adopted the old plan of provoking, by means of paid emissaries, an outbreak which would place the leading Reformers in their power.

The Cato Street conspiracy, for which Thistlewood and four of his associates were hanged, was organised by a Government spy called Edwards, and, as we shall see, the “Battle” of Bonnymuir was the result of a plot in which the leading movers were creatures of the double-dyed traitor, Richmond. An association was formed in Glasgow, and communications opened with the London Committee, of which Edwards the spy was a member. This Committee issued orders to the committees in Glasgow and other parts of Scotland to summon all their host, to have the people prepared to seize their lost rights, and be ready to follow up victory as they should be further instructed.

About the end of March a meeting of delegates assembled in the house of Robert Mackenzie, Bishop Street, Anderston, and a man named Lees, probable an agent of Richmond, who was working behind the scenes, suggested that each of those present should come prepared next night with the draft of an Address, calling on their countrymen to vindicate their rights, as, he said, their friends were about to do in England. The delegates, however, had simply met to discuss the news of the day, and had no intention of taking part in any rising. They did not entertain Lees’ suggestion favourable, and the matter dropped.

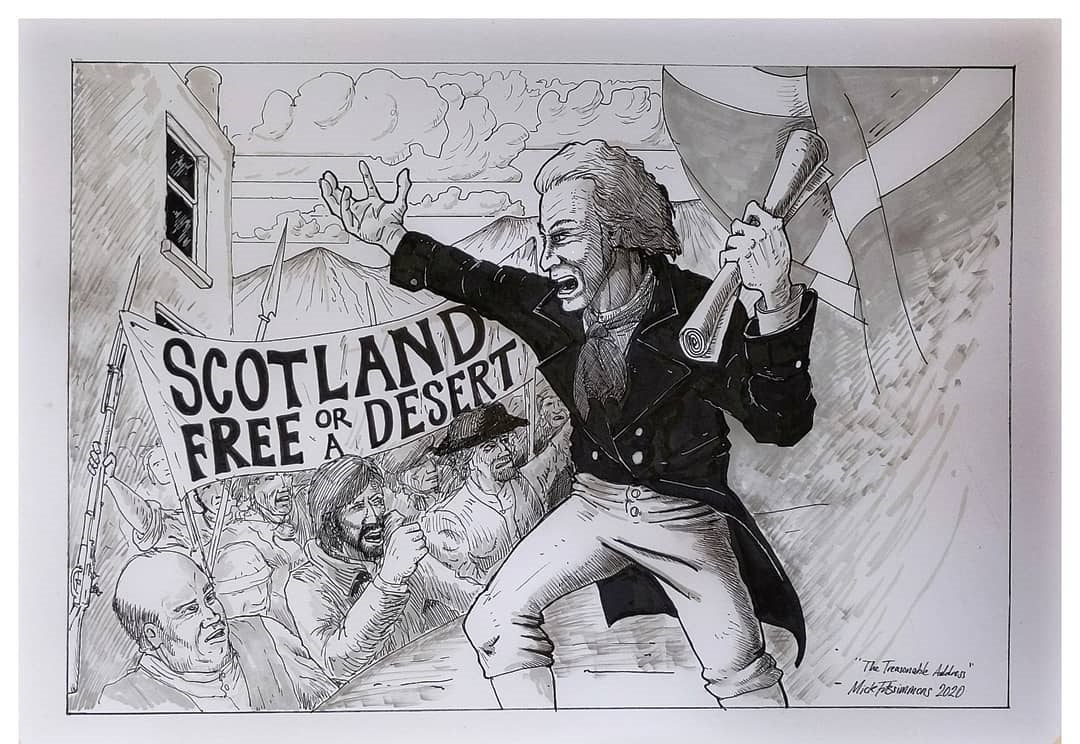

On the 30th March this Lees met a printer named Fulton, in the Globe Tavern in the Saltmarket, and gave him a paper which he had concealed between his stocking and his leg. This was the treasonable Address which startled the country on Sunday 2nd April, and which was the foundation of the case against Baird and Hardie. It, in fact, sealed their doom. We will give the text of the Address in our next chapter, but meanwhile it is important to observe that neither Baird nor Hardie knew anything about it before it was published. There can be little doubt now that the paper given to the printer by Lees was written by the author of the “treasonable oath” of 1817, namely, Richmond the Spy.

He tells us in his “Narrative” that the local authorities were aware for some days previous of what was going forward, but the policy adopted was to get thoughtless people to commit themselves. Peter Mackenzie asserts that a copy of the treasonable Address was in the hands of the Magistrates of Glasgow on the Friday, twenty-four hours before it was put up or published in the city. He also says that a high legal functionary in Glasgow (the Sheriff, no doubt) caused orders to be issued to the public not to hinder or apprehend any person sticking up bills through the streets in the course of Saturday night. Next morning the Address appeared on the walls of the city, and simultaneously copies were posted up in Paisley, Kilmarnock, Govan, Strathaven, Hamilton, Airdrie, Kilsyth, and Dumbarton, a circuit of twenty or thirty miles round Glasgow.

(To be continued…)