A pre-review of David Smale’s new book on the Radical War of 1820

The current issue of History Scotland (March/April 2021) has an article by Dr David Smale outlining the research findings that he presents in his forthcoming book titled The Radical War of 1820: Police Spies, Government Spies and Willing Informers, due to be published later this year.

This book, and the claims that it makes, are of significant interest to historians and scholars of the radical war of 1820 on at least three counts. Firstly, it seems that the material uncovered by Smale is of great relevance to the ongoing and as-yet-unresolved debate surrounding the role of political informers, police spies and government agents in the Radical War of 1820. Secondly, from the mere taster provided by the article, it would seem that this book may shed some light on the mystery of the central committee, and the arrest of its members in a Glasgow Tavern on the 22nd February 1820. Thirdly, the thinly obfuscated political function of the Lord Advocate is further exposed, laying bare the myth of ‘neutrality’ and the liberal lie that underpins any notion that such high office, in any country and in any political context, could act independently of the dominant political force that appoints it. Although, to be fair to Smale, this may not be a view he shares with us on the political role of the incumbent Lord Advocate or his vast array of predecessors.

Smale’s own background, as a Royal Marine and former officer in the Lothian and Borders Police Force, makes his book a very interesting prospect, since few historians will share the unique perspective arising from his own professional ‘habitus’.

Smale points out the fundamental truth behind this controversial issue, by highlighting the fact that the very nature of spying makes research extremely difficult since the ‘records are patchy oblique and confusing’. He does however, make the claim that, despite the challenges, it is possible to detect at least five different spy groups.

These are represented by the following;

The Lord Advocate and his Police Spies

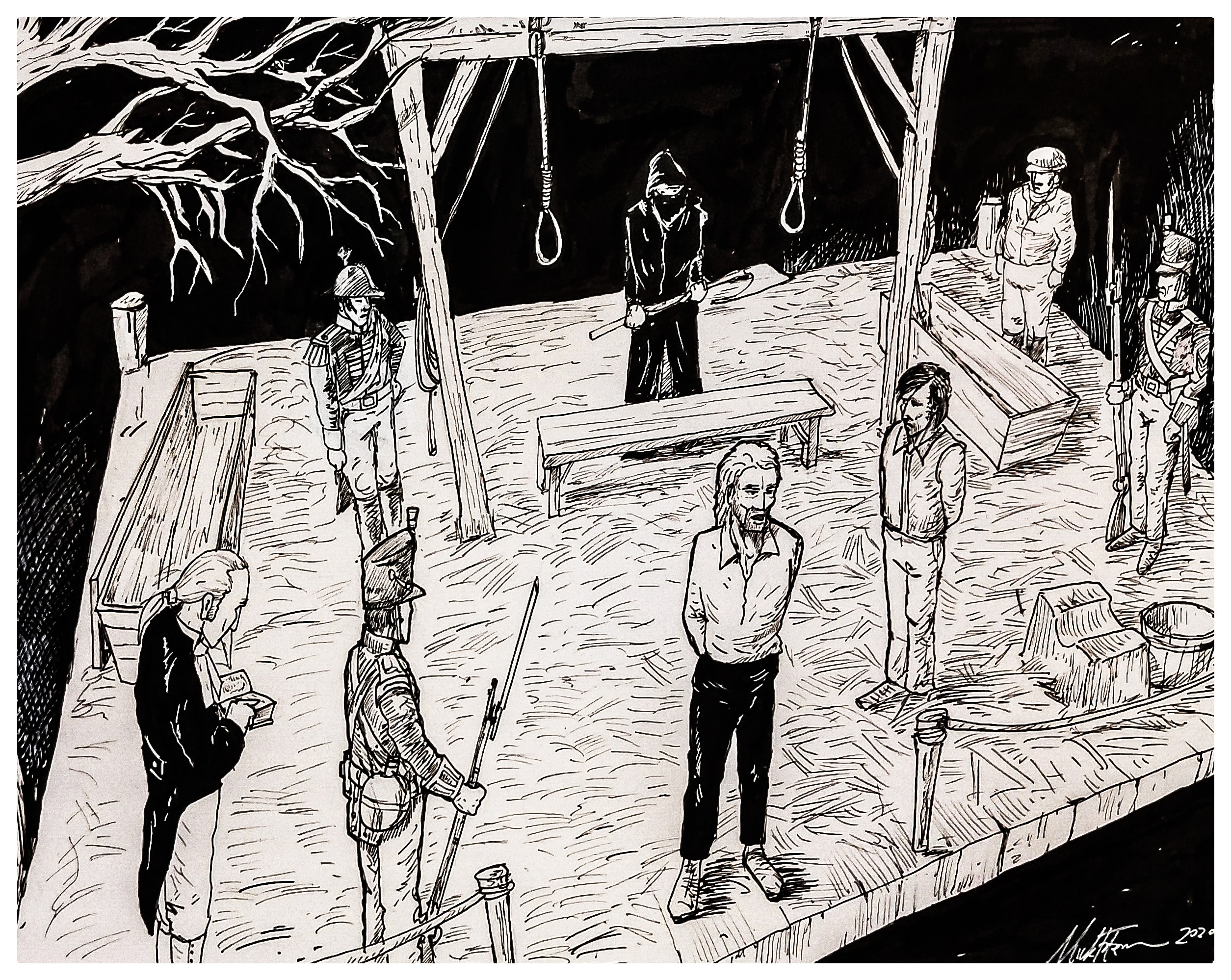

As early as 1816, Lord Advocate Alexander Maconochie had informants on the radicals’ committee in Glasgow as well as receiving intelligence from Linlithgow’s head constable McKay. In 1819 the new Lord Advocate William Rae continued to use Maconochie’s spy network, a group so successful in infiltrating the radicals that they were able to obtain seats on the central committee from August 1819 until January 1820. Thus, information was fed to the Lord Advocate who in turn furnished the Home Secretary Sidmouth with detailed accounts of the activities and plans of the radicals; evidence that led to the arrest, on the 22nd February 1820, of the 27 people ‘stilling (sic) themselves Radical Reformers who met in a small tavern in this city… a central committee.’ This, as Smale concludes, cut the head off the radical movement and severely disrupted their plans for a radical rising.

‘Secret Men’

In August 1816, the officers’ committee and the secret service committee decided to deploy undercover officers, ‘three persons of intelligence and activity and who can write a fair hand’. The police minute books show that McGregor, Paterson and Linlithgow were employed, although it seems likely that a number of other Glasgow police officers were also used as spies. After the threat of rebellion subdued, Mathew Legat, senior criminal officer in the Glasgow Police, emerges from the record as a significant spy-master running a number of paid informants during the period leading up to April 1820.

The Sheriff and his Spy

George Biggar was employed as a spy by Sheriff Robert Hamilton of Lanarkshire. Smale suggests this was to counter the propensity of other spies to exaggerate and fabricate evidence. Biggar had been admitted into the inner circle of the radicals and provided a wealth of intelligence on a range of matters including the signs, handshakes and passwords that identified the reformers.

The Home Secretary and his Informants

Smale’s examination of the Home Secretary’s correspondence revealed a steady stream of letters between himself and a range of informants wishing to sell information on the radicals and their activities. Some of these letters contained information pertaining to the manufacture of metal objects (throwing-darts) as well as pike heads and the removal of a great number of ash trees for the staffs of such pikes.

The MP and his Spy

Alexander Richmond, radical sympathiser turned informer, ran his own network of spies, two of whom, McLachlan and Macdowal Peat, had infiltrated the radicals’ inner organisational structures. Richmond in turn passed the intelligence to Kirkman Finlay, Provost and Member of Parliament, who forwarded the information to the Lord Advocate, and eventually it arrived on Sidmouth’s desk.

Agents Provocateurs

Smale concludes the article by drawing attention to the importance of trying to assess the extent to which the spies acted as agents provocateurs. Here he discusses Peter Mackenzie’s book and points out that the spy called King (also called Andrews), who it is claimed encouraged Baird and Hardie to march on the Carron Iron Works remains elusive. Neither he nor James Shields who was supposed to have duped the Strathaven weavers appear in the primary sources.

Interestingly Smale goes on to say that, “understanding the situation has been complicated by later accounts with a socialist or nationalist interpretation which emphasises the emergence of a working class in the first general strike, or an attempt to end the union and form a Scottish government.”

The article ends by highlighting the uncertainty remaining over the extent to which the spies instigated the uprising, but what is not debatable, he says, is the success of the police spies. The central committee was thoroughly infiltrated, Smale claims, and their plans were fed up the chain of command, ultimately to Sidmouth. In contrast to the recent works by Murray Armstrong and Maggie Craig and to a slightly lesser extent, Kenny McKaskill, Smale seems to be in absolutely no doubt that the defeat of the Radicals and reformers was ultimately down to the Georgian state’s use of its most effective traditional tool, the spy.